File download is hosted on Megaupload

(Note: This is part of a larger project chronicling the history of punk rock in Marin County, California during the 1980’s.)

The atmosphere was somber at the Sleeping Lady Café. It was September, in the year of Orwell – 1984 – and Ricky Paul, the lead singer for the Pukes had recently hanged himself, dying at the age of 22. The young people gathered that evening were there to remember, mourn and share their grief over his passing. Erik Meade, one-time member of the Pukes and other Marin bands, summed up the feelings of many when he said that along with Ricky, the Marin punk scene had died. The sentiment, while not literally true, successfully conveys Ricky Paul’s central importance for Marin punk during the early 1980’s.

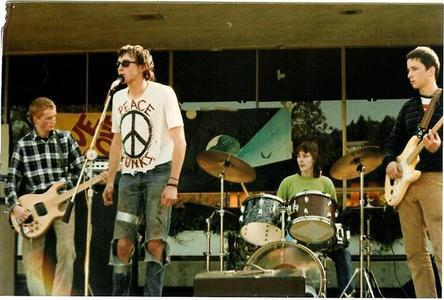

The Pukes at College of Marin, c. 1983: (From left to right) Brook Johnson, Ricky Paul, Nicky Poli, and Mark Wolf

Creative, friendly and full of enthusiasm, Ricky was known and loved by just about everyone. His band The Pukes played often in Marin and in San Francisco. Whether at house parties or clubs, they always attracted a large throng of young, enthusiastic fans. The Pukes were so named because Ricky had the talent of being able to vomit on demand at key points during performances, to the delight – and often the horror – of those in the audience. Wolfing down large quantities of pizza or other junk food before getting on stage, Ricky would then stick his finger down his throat halfway through the set and upchuck, providing visual punctuation for the lyrics of one song or another.

“It always grossed us out, but it was the one thing that set us apart from other punk bands, so we never complained,” remembers Brook Johnson, founding member and bass player for the Pukes.

Audience members unprepared for the messy display inevitably recoiled in shock and disgust, sometimes experiencing something close to trauma.

“I’ll never be able to look at him the same way again,” one of Ricky’s College of Marin classmates, Kent Daniels, once lamented, his face flushed white in shock after witnessing the voluntary vomit launch for the first time.

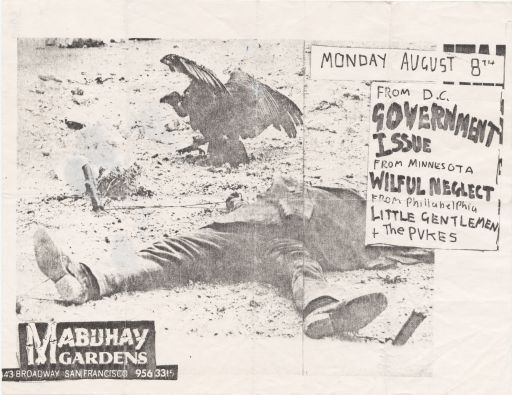

Walter Glaser, back-up vocalist for the Pukes, and later, after Ricky’s death, the lead singer, recalled a show at the Mabuhay Gardens in San Francisco when Ricky, after vomiting on stage, began throwing the mess at audience members; including a group of skinheads. “All the skinheads basically ran out of the club, which was hilarious, because they were the notorious ‘tough guys’ of their day. I remember the skinheads coming back in after we were done and I was scared they were going to kill us. But they didn’t. Instead, one guy, ‘Crazy Horse,’ introduced himself and said he thought we were cool!”

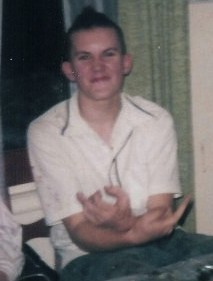

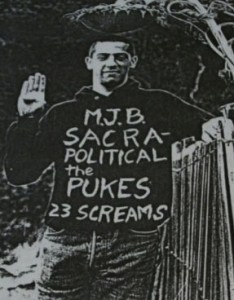

When he wasn’t puking on stage and screeching punk rock lyrics, Ricky spoke in a nasally, hoarse but gentle voice; described by one interviewer as half the time like “a 331/3 at 45, the other half like a 45 at 331/3.” He was thin and wispy in build, with hair of changing colors; sometimes shorn into a crew cut, sometimes grown out long and unkempt, sometimes fashioned into a mohawk. In a 1983 profile appearing in the Music Calender, Rebecca Solnit described him as “a self-acknowledged wimp. …a pale boy with prominent, fragile bones and eyes like myopic morning glories. His voice conveys his sincerity. It’s soft and hoarse, the aural equivalent of out-of-focus.”

In contrast to his onstage persona, which was outrageous and confrontational, offstage Ricky was sensitive, tender and sweet with his friends and comrades. Juneko Robinson remembers the first time she met Ricky when he approached her at a Marin County bus stop. Recognizing her as a fellow punk, Ricky greeted her excitedly, exclaiming “Hey, punk rock!” before offering to share his peanut butter and jelly sandwich. There was something child-like and innocent about him, she remembers, even if when performing he had an unruly lack of inhibition.

When it came to confronting bullies, however, Walter Glaser remembers that Ricky was assertive, standing up for himself and unhesitant to tell them “to ‘fuck off’ to their face even when it seemed disadvantageous to do so.” He wasn’t gentle or a wimp when it came to “fighting against things that he thought were wrong in the world.” It seems that the anger and outrage that Ricky channeled into his onstage performances could also come out on the street if there was enough provocation; for example, when he once deliberately puked on the hood of a car occupied by one of his high school enemies!

So there was not such a clear incongruity between his on- and off-stage personae after all. Performing was just his opportunity to share with a sympathetic audience something of his own real-life disgust with the injustices of the world. Indeed, Ricky claimed that his Jewish identity and his identity as a punk were connected, as both groups are “oppressed minorities,” with a duty to confront and challenge a society that misunderstands and derides them. He felt that minorities and punks needed to make their voices heard. He thought speaking the truth about oppression was an act of rebellion against those who didn’t want to listen, who wanted to block their ears to the anger and distress of the outcast. Singing in a punk rock band, then, was the perfect outlet for those most authentic emotions that Ricky was struggling with throughout his life, and the band, rather than being a sideline, was central to who he was. As he once said in an interview, “It’s honest, the most honest thing there is.”

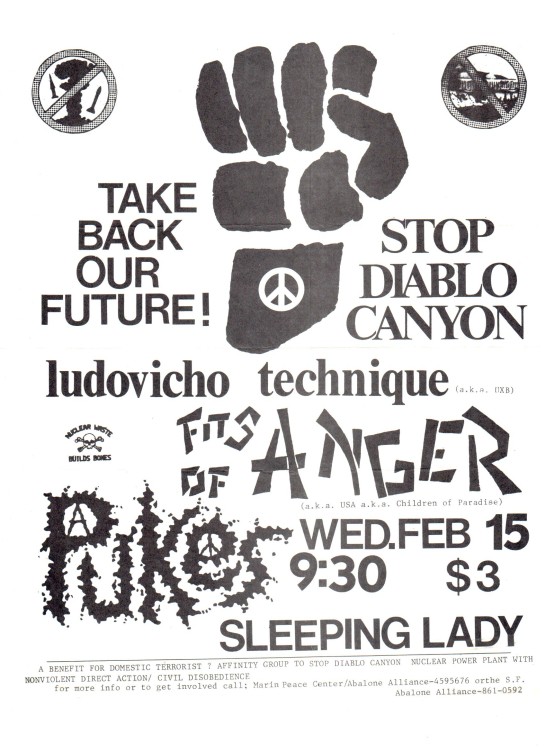

“Ricky once told me that the Pukes were his life,” recalls Brook Johnson. Brook had first been introduced to punk as a high school freshman in 1981 when he saw the Ramones play in Sonoma County. The next year he and his friend Mark Wolf started to talk about forming a punk band, and when they met Ricky things quickly came together. Sporting a green mohawk and possessing an enthusiastic, do-it-yourself attitude, Ricky wanted nothing more than to front the group as lead singer. Lacking a drummer, he encouraged his friend Nicky Poli to learn how to play and to join the band as well. Thus The Pukes were born. Within a month, they had developed something resembling a set of songs and played their first gig at the Sleeping Lady Café in Fairfax, opening for another Marin punk band, U.X.B.

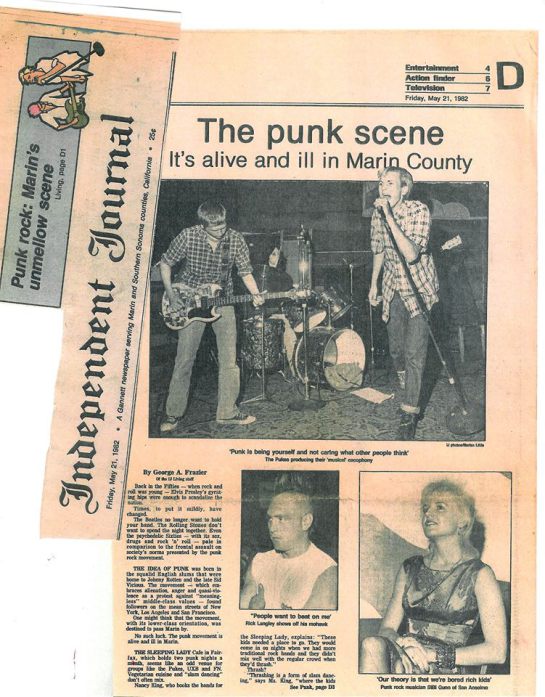

“We sounded terrible,” says Brook, “but a reporter from a local newspaper, The Marin Independent Journal, was there and did a story on us along with a photo.” In that article, the author, George A. Frasier offered his own assessment of the Pukes: “Primitive is not the word for the Pukes. They produce a cacophony that would send almost anyone over the age of 30 running from the room.” Despite (or because?) of this, the Pukes became something of a local legend, with people thereafter recognizing them as “that band with the singer who pukes on stage.”

Some of the songs played by The Pukes were just flat-out noisy, with Ricky moaning and screeching incomprehensibly against a background of droning guitar, bass and clunky drumbeats. “Sometimes he would freestyle the lyrics, making them up as he went along.” But they also developed more polished songs like Parents, or The Question Is?, which had an upbeat, catchy sound that successfully harnessed the raw energy and anarchic nature of the group’s talent to great effect.

There was nothing despairing or sad about The Pukes’ music. Even as Ricky spewed anger at his parents, the police, or at jocks, their mood was consistently buoyant, inspiring fans to dance, laugh and interact with the band. Part of this probably had to do with the fact that through this music audience and performers found solidarity and unity against common enemies. The song Parents complained about the bane of all teenagers: chores and rules set down by mom and dad. A song like Macho took good humored jabs at the jocks and tough guys who were the natural foes of punks in Marin, while Red Badge of Courage used the title’s literary allusion to comment on the ongoing hostility between punks and the police. If you didn’t listen closely to their music, it might be easy to dismiss it all as noisy, mindless punk rock. But once you really gave them your attention, it became clear that they were doing more than just making a racket. They were actually making a statement. Their music was social and cultural commentary done in true punk style, conveying what it was like to live as a punk in Marin County.

The song S and M Waltz was a particularly good illustration of how the Pukes gave voice to the Marin experience. It poked fun at the image of Marin punks as softies, as coddled residents of one of America’s richest counties, living in the seat of luxury and who were thus perceived as less “hardcore” than punks from San Francisco or from Huntington Beach:

“We’re not from San Francisco, or Huntington Beach!

This is the S and M Waltz;

Sonoma and Marin,

And we always dance the Waltz, no matter what county we’re in.

We do not thrash, and we do not bash!

We dance the S and M Waltz, around and around,

We like the Waltz, and the 3, 4 sound.

We like to waltz,

All day long.

But we do not thrash, ‘cause we are not strong.

We’re not from San Francisco, or Huntington Beach!

This is the S and M Waltz,

Dance it if you can.

We know you can’t,

‘Cause you’re such a Man.

We’re not from San Francisco, or Huntington Beach!’

These lyrics were delivered against a punked-up, “oom-pah-pah” musical backdrop that encouraged audience members to join together in pairs and perform an exaggerated version of the waltz, frantically running in circles about the dance floor. It all had an aggressive yet silly and fun-loving feel to it that resonated perfectly with the image of the Pukes themselves.

Toward the end of his life, Ricky became increasingly fascinated with beatnik culture and art, adapting his appearance with the addition of a beret and learning how to play the saxophone and bongo drums. This new interest served as his motivation to begin attending the San Francisco Art Institute.

Brook Johnson and Walter Alter both remember Ricky expressing irritation with the San Francisco art scene after he started attending the Art Institute. “He told me he had become disillusioned with the teaching approach and the negative, nihilistic work that was being encouraged by the faculty,” Walter Alter writes. “The last time I saw him several days before his death he looked worried and distracted, like something was up.”

Apparently Ricky would sometimes spend the night in Studio 8A of the Institute, which is where he was found hanged in September of 1984.

Brook recalls learning of Ricky’s death from Mark Ropiquet (AKA “Snoopy”) –then guitar player for the Pukes – after Ricky failed to show up for a scheduled film shoot. The true circumstances of his death are still a matter of controversy for those close to him, with speculations ranging from suicide, to auto-erotic asphyxiation, to a performance art piece gone wrong. Whatever the real truth, in the end it all amounted to the same thing: Ricky was gone, leaving his family and friends to mourn his passing, and his musical collaborators to struggle with how to carry on and to honor his memory in the future.

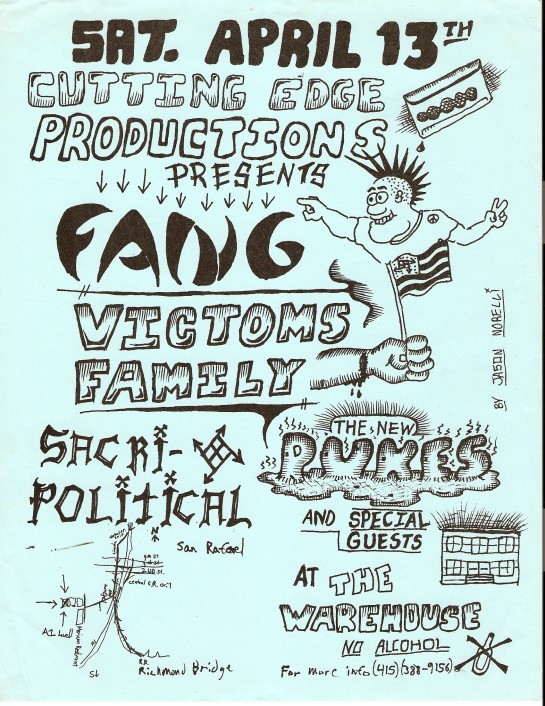

The Pukes didn’t die with Ricky, but they were transformed. Walter Glaser stepped in as lead singer and Dave Lister took over as guitarist. “In retrospect, I think we should have changed our name to something else. You could say we kept it out of respect for Rick,” Brook explains, echoing a sentiment also expressed by Walter: “Ricky was not only my bandmate, but also a good friend, a Marin punk legend and really, an inspiration to me. No one could fill Ricky’s shoes. We kept the band going out of respect for him.”

The “New” Pukes wrote an original set of songs and continued to perform at venues in Marin and San Francisco. There was no more on-stage vomiting, but Walter had his own hilarious stage presence, altogether different from that of Ricky Paul. He sported a simple, down-to-earth style, with cropped black hair and a wardrobe rarely deviating from t-shirt and blue jeans. He would bounce around the stage – sometimes being silly, sometimes aggressively confronting audience members – all the while making exaggerated faces and hand gestures reminiscent of the Don Martin cartoon character Mr. Fonebone from Mad Magazine. His voice, like Ricky’s, was nasal and came from the back of the throat, but it was less high pitched, sounding more like the growl of coyote than the shriek of bobcat. His lyrics continued to lash out at familiar targets, but instead of parents and cops, now they denounced asshole drivers, tedious loudmouths, and the patrons at one of Marin’s popular punk gathering places, Café Nuvo:

I’m so hardcore, don’t you know,

‘Cause I hang out at Café Nuvo.

Everyone knows how punk I am,

Then I go home and listen to Duran Duran.

I got my boots for 35,

And I’m the toughest guy alive.

I need some pot so gimmee some dough.

I think punk rock is a fashion show.

Think I’ll go scam on a chick,

And brag about my 10 foot dick.

Picking up girls is such a gas,

So I can get a piece of ass.

These are the people that make me ill,

To the point that I could kill.

Stupid attitude I can’t bear,

They’re just fuckin’ jocks with short hair.

Walter says that all of the shows he played with the “New” Pukes were “really fun,” especially when the audience was filled with lots of friends. “The Pukes were a pretty beloved band amongst a small group of people.” That was certainly true; and it remained true all the way up until their final breakup sometime in the late 1980’s.

Sources:

Alter, Walter. “The Death of Ricky Puke,” (Blog posting). <http://gordonzola.livejournal.com/125133.html > Last accessed 3/13/18.

Anonymous. “Odd One Out,” (Newspaper article. Source and date unknown.)

Cornell University Library Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections. <https://digital.library.cornell.edu/collections/punkflyers>

Daniels, Kent. Interview with John Marmysz. December 17, 2018.

Frazler, George A. “The Punk Scene: It’s Alive and Ill in Marin County,” in Independent Journal, Friday, May 21 1982.

Glaser, Walter. Interview with John Marmysz. March 7, 2018.

Johnson, Brooke. Interview with John Marmysz. February 2, 2018.

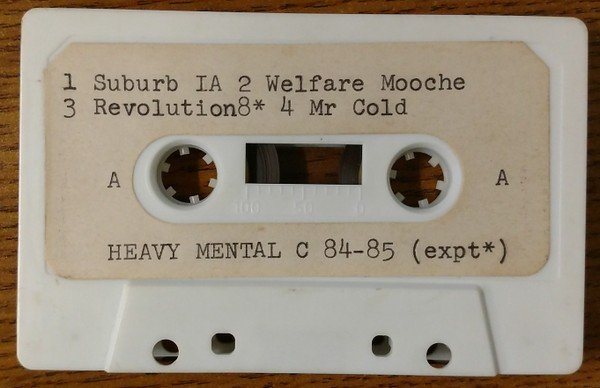

Marin Underground (Compilation tape. c. 1985.)

Meade, Erik. (Myspace Page). < https://myspace.com/erik_meade/mixes/classic-the-pukes-friends-362755/photo/91231825> Last accessed 3/13/18.

Pukes Demo Tape. < https://youtu.be/j3onVSzX354> Last accessed 3/13/18.

Robinson, Juneko. Interview with John Marmysz. January 3, 2018.

Solnit, Rebecca. “Marin Punk Explained!” Music Calendar, November 1983.