File download is hosted on Megaupload

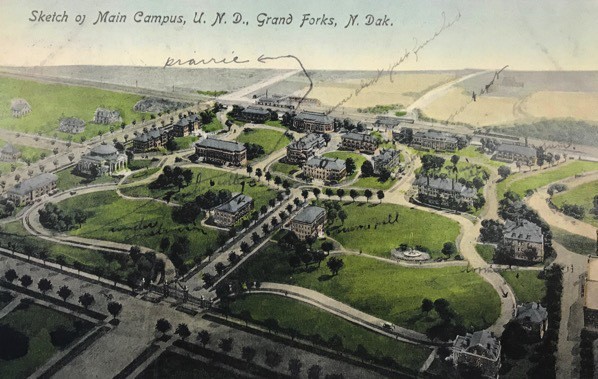

On Friday, I did a walk through of two buildings on the University of North Dakota campus that are slated for demolition this spring. While their fate is sealed, I’m excited to collaborate with students and colleagues on documenting these buildings as part of a one-credit class. Our work will obviously focus on these buildings as historical structures associated with Wesley College, an experiment in co-institutional education from the early 20th century, and as examples of a Beaux Arts university plan that failed to materialize.

The walk-through on Friday, however, reveled a different, and more archaeological, aspect to our research. The buildings are still filled with stuff (or to use a more appropriate term, borrowed from Philip K. Dick “kipple”). In the case of Corwin/Larimore and Sayre halls, built between 1908 and 1910, the departments and programs housed in this building departed before the start of the academic year. This has led me to several research opportunities:

1. Surplus. The departing departments and programs left behind a remarkable assemblage of “stuff” designed for institutional repurposing through centralized surplus. It just so happens that as part of a greater reorganization of UND’s space and campus services, centralized surplus storage and redistribution is no longer available at scale for UND’s campus. As a result, this material is stuck in limbo. It had so little value that it was simply discarded in place by the departing faculty and staff, and there is no institutional infrastructure for recycling or repurposing this material. At present, it simply remains in place, awaiting documentation as evidence for the abandonment of these buildings.

2. Trash. The rooms and spaces also contained a remarkable amount of material that has very limited value as recycled goods. We can best designate this material “trash.” The trash ranged from stacks of papers scattered across a table that hinted at their former order to damage furniture, obsolete equipment (VCRs, CRT monitors, tangled masses of cables, et c.), easily replaced personal objects like pens and pencils, posters, and articles of clothing.

While the presence of surplus equipment represents both institutional priorities and the intermediate character of the abandonment of these buildings, trash represents permanent discard. There is no intention of collecting this trash and it will likely remain in situ as the building is physically destroyed. Moreover it tells a different story of abandonment as a process.

3. The Percolating Past. The attention to the present and abandonment as part of the history of the building is not meant to obscure the past of these buildings, but to make it clear that the creation of the past in these buildings is part of an ongoing process that reshapes the structures through time. What we encounter as the historical aspects of these buildings, including the traces of their original floor plans, evidence for past modifications and updates, and hints of successive functions in each space, is the same as the evidence for their abandonment. The past percolates (as Shanks and Pearson once quipped) through the present and the present will see similar filtering practices to constitute a future. Our work to document the present and past of these buildings speaks directly to the complex system of interventions, priorities, and agents at play in shaping our material reality. While any hope of dis-entangling these networks of past and present agency, objects, and situations maybe misplaced, getting students (and myself) at least to recognize the various ways

4. Global Buildings. The buildings and their contents represent a dense network of relationships the span the continent and the world. Of course, it will only be possible to sketch out these relationships on a very basic level, but some of the most intriguing ties are between the funds to build these buildings and various west coast timber interests. Frank Lynch and A.J. Sayre both supported Wesley College, in part, through donations supported by their ownership of lumber rights in California and British Columbia respectively. Agricultural wealth from the Larimore and Sayre family likewise bolstered Wesley College coffers. The architect, Wallace McCrae hailed from New York City where he goes on to build brownstones for the wealthy and famous of the Gilded Age. The buildings themselves embraced the Beaux Arts tradition that was similarly cosmopolitan. The students who frequented these halls for over a century intersected with these global currents.

Today, the buildings participate in another network of global relationships the fill these spaces with objects that originate across the U.S. and the world to create functional assemblages only depleted by these building’s abandoned state.

5. Modernity. Finally, it’s hard not to think of these buildings as the embodiment of the long-20th century starting with their Beaux-Arts design and continuing to their eventual fate as victims of progress. As Kostis Kourelis has been teaching us, Beaux Arts campuses of the early 20th century represented the cutting edge of campus architecture, and the (largely unrealized) plan for UND, which by the second decade of the 20th century had committed to College Gothic architecture. There is something remarkably optimistic about these buildings.

The destruction of these buildings embodies a similar spirit that looks beyond the bricks-and-mortar and their persistent, draining expenses, and toward a leaner, more digital, more efficient university that leverages whatever technology we’ve decided to see as the solution to whatever problem we’ve decided to prioritize. As I’ve argued elsewhere the demolition of these buildings is fully in keeping with an effort to display the university as an efficient, forward looking, in unsentimental, institution. As the kids would say, “This is a ‘billboard move,‘ brah.” Whether it’s the right choice or not, will come out over the long term.

I’ve created a Wesley College category for these and other posts like it.