File download is hosted on Megaupload

Bernard Reginster’s book The Affirmation of Life: Nietzsche on Overcoming Nihilism is an ambitious and thorough work. It proposes an interpretation of Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophy that emphasizes its orderly and logical structure, portryaing it as a consistent and coherent system offering a solution to the problem of nihilism and a strategy for the affirmation of life. Both in its purpose and tone, Reginster’s book reminds me of other works that approach continental thinkers and themes from a self-consciously analytic perspective; books such as David E. Cooper’s Existentialism, Antoine Panaïoti’s Nietzsche and Buddhist Philosophy, and James Tartaglia’s Philosophy in a Meaningless Life. The Affirmation of Life sits alongside these other efforts as a well-argued attempt to bring some order to what can sometimes seem like a very disorderly and unruly topic.

Bernard Reginster’s book The Affirmation of Life: Nietzsche on Overcoming Nihilism is an ambitious and thorough work. It proposes an interpretation of Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophy that emphasizes its orderly and logical structure, portryaing it as a consistent and coherent system offering a solution to the problem of nihilism and a strategy for the affirmation of life. Both in its purpose and tone, Reginster’s book reminds me of other works that approach continental thinkers and themes from a self-consciously analytic perspective; books such as David E. Cooper’s Existentialism, Antoine Panaïoti’s Nietzsche and Buddhist Philosophy, and James Tartaglia’s Philosophy in a Meaningless Life. The Affirmation of Life sits alongside these other efforts as a well-argued attempt to bring some order to what can sometimes seem like a very disorderly and unruly topic.

Reginster points out in the introduction to The Affirmation of Life that interpreters of Nietzsche generally fall into two categories. On the one hand, there are those who approach his writings piecemeal, taking his aphoristic style as evidence that Nietzsche never meant readers to think systematically about his work, but rather to read his books as a kind of poetry that plays with recurring themes, observations and insights. Like the musings of a insightful but scattered mind, this approach treats Nietzsche’s books as compendiums of ideas and thoughts lacking system or method. Nietzsche does encourage this sort of reading at times; for instance in Twilight of the Idols writing, “I mistrust all systematizers and avoid them. The will to a system is a lack of integrity.” (I 26)

On the other hand, there are those who approach Nietzsche more “globally,” focusing on a theme or doctrine that is taken as playing a unifying role in his overarching philosophical system. In this approach, the variety of ideas appearing throughout Nietzsche’s books are taken as logically connected parts that hang together with regularity and order. In these sorts of interpretations, one particular doctrine is generally thought to be the key to unlocking the real meaning of Nietzschean philosophy; whether it be the revaluation of values, the Superman, the eternal return, or the will to power. For these kinds of interpreters, Nietzsche’s writing style and his periodic denunciations of systematic thinking are distractions from the actual, underlying structure of his thinking process, which can be reconstructed by looking at the overall trajectory of his life work. If you do this, so it is claimed, one will discover that Nietzsche was concerned with thinking through some particular sort of problem in an orderly and deliberate manner.

Reginster’s reading of Nietzsche is aligned with the latter approach. However, unlike past interpreters he tells us that it is not a particular doctrine that lies at the center of Nietzsche’s philosophy, but a “particular problem or crisis.” (p. 4) This problem is the “crisis of nihilism,” which, in its most general sense, is “the belief that existence is meaningless.” (p. 21) Nihilism is marked by the distressing loss of confidence in goals and ideals that once gave human life meaning and purpose. Nietzsche’s writings are mostly concerned with nihilism as a European crisis; a problem that emerges in modern times with the increasing erosion of Judeo-Christian beliefs. This devaluation of traditional beliefs is a problem since, as of yet, nothing has emerged to take their place, and thus meaninglessness and lack of purpose threaten to infect European culture. According to Reginster, Nietzsche’s entire philosophical project is an attempt to address this threat and to offer a replacement for these lost values.

Reginster’s reading of Nietzsche is aligned with the latter approach. However, unlike past interpreters he tells us that it is not a particular doctrine that lies at the center of Nietzsche’s philosophy, but a “particular problem or crisis.” (p. 4) This problem is the “crisis of nihilism,” which, in its most general sense, is “the belief that existence is meaningless.” (p. 21) Nihilism is marked by the distressing loss of confidence in goals and ideals that once gave human life meaning and purpose. Nietzsche’s writings are mostly concerned with nihilism as a European crisis; a problem that emerges in modern times with the increasing erosion of Judeo-Christian beliefs. This devaluation of traditional beliefs is a problem since, as of yet, nothing has emerged to take their place, and thus meaninglessness and lack of purpose threaten to infect European culture. According to Reginster, Nietzsche’s entire philosophical project is an attempt to address this threat and to offer a replacement for these lost values.

Reginster identifies two variants of nihilism. The first variant emerges from the devaluation of goals that at one time actually did give life meaning and purpose. The second variant is rooted in the conviction that any goals that could give life meaning and purpose are in fact unrealizable. In the first instance, nihilism emerges along with the realization that the things we once valued – our highest aspirations – are now things that have lost their value for us. So, for instance, a person might at one point in time value the aspiration toward being rich, but then at some later point in life come to the realization that money-making is not really all that important, and thus that the life he or she currently lives has become meaningless. The second kind of nihilism has less to do with the content of particular goals themselves, but with their realizability or attainability. So, for instance, a person might continue to aspire toward, and value, becoming rich, but come to realize that it is, in fact, impossible to actually achieve riches. The goal is not realizable even though it continues to be desired, and so, once again, life becomes meaningless.

Reginster argues that for Nietzsche, in order for life to be meaningful, our goals must both be valuable and realizable. To avoid nihilism, then, the purposes and projects we embrace must have the possibility of actually being accomplished. Otherwise, we will either become disoriented or fall into despair. Nihilistic disorientation is connected to the conviction that the highest human values are no longer valuable, while nihilistic despair is connected to the conviction that the highest human values are unobtainable because they are not objectively real, but rather illusory projections of the human mind.

Nietzsche’s own conception of nihilism, Reginster claims, is ambiguous in the sense that his writings equivocate between addressing nihilism as disorientation and addressing nihilism as despair. The problem is that these two senses of nihilism actually seem to conflict with one another, since if one no longer values a goal, then its unattainability would not be a source of distress, and, on the other hand, if a goal can’t be realized, then by its very nature it becomes drained of value. In other words, if one is a disoriented nihilist, then there is no reason for one to also be a despairing nihilist, and vice versa. If you don’t value riches, for instance, then you won’t even care that they can’t be achieved. And, if you know that you can’t be rich, then the desirability of aspiring toward riches will vanish. Reginster argues that most interpreters underemphasize the ambiguity in Nietzsche’s understanding of nihilism, but that nonetheless it is key to understanding his strategy for affirming life and overcoming both despair and disorientation.

The crux of Nietzsche’s strategy is, first, to reveal the groundlessness of traditional values and, second, to introduce a new highest standard of attainable values based on the will to power. So, the overcoming of nihilism proceeds in stages. The first stage involves revealing that the highest values currently driving western culture to nihilistic despair – Judeo-Christian values – lack objective standing. Since they are not objectively “real,” Judeo-Christian values are illusions that are “life-negating” in the sense that they encourage us to pursue goals that are unattainable (such as everlasting life in heaven). Revealing the inherent unrealizability of the values implied by this belief system undermines their value, and so this first stage of Nietzsche’s strategy liberates us from Juedo-Christian nihilism as despair. By revealing the illusory, and thus unattainable, nature of things like God and heaven, their desirability as aspirational goals vanishes. However, the elimination of these traditional values in turn provokes nihilistic disorientation. With the death of God, a void is left in place of the highest (unattainable) values, and the entire moral order that was implied by God’s existence collapses. We are robbed of our highest (unattainable) goals and aspirations, and life becomes, once again, meaningless insofar as there is no organizing center, no ultimate guiding purpose to life. Nihilism as disorientation is thus introduced.

The crux of Nietzsche’s strategy is, first, to reveal the groundlessness of traditional values and, second, to introduce a new highest standard of attainable values based on the will to power. So, the overcoming of nihilism proceeds in stages. The first stage involves revealing that the highest values currently driving western culture to nihilistic despair – Judeo-Christian values – lack objective standing. Since they are not objectively “real,” Judeo-Christian values are illusions that are “life-negating” in the sense that they encourage us to pursue goals that are unattainable (such as everlasting life in heaven). Revealing the inherent unrealizability of the values implied by this belief system undermines their value, and so this first stage of Nietzsche’s strategy liberates us from Juedo-Christian nihilism as despair. By revealing the illusory, and thus unattainable, nature of things like God and heaven, their desirability as aspirational goals vanishes. However, the elimination of these traditional values in turn provokes nihilistic disorientation. With the death of God, a void is left in place of the highest (unattainable) values, and the entire moral order that was implied by God’s existence collapses. We are robbed of our highest (unattainable) goals and aspirations, and life becomes, once again, meaningless insofar as there is no organizing center, no ultimate guiding purpose to life. Nihilism as disorientation is thus introduced.

The second stage in Nietzsche’s strategy is to offer a revaluation, showing that “life-negating values are not the highest values.” (p. 50) He does this, according to Reginster, by proposing the will to power as a replacement for the highest “principle” or ethical “standard” (p. 148). What this accomplishes is to introduce a this-worldly, attainable standard of value, as opposed to the other-worldly, unattainable standard advocated in the Judeo-Christian tradition. The main barrier in the way of advocating this new standard, however, is “the problem of suffering” (p. 159). Influenced by his reading of Schopenhauer, Nietzsche regards this problem as the issue uniting all western (and some non-western) moral systems. Whether it is Christianity, Buddhism, Utilitarianism, or Eudaimonism, the condemnation of suffering seems universal. But if, as all of these systems claim, suffering is an evil that to some degree will always remains a part of our life in this world, then the goal of eliminating suffering is itself nihilistic, since it involves the pursuit of something that can never be actually and fully realized in the here-and-now. All of those moral systems advocating the end of suffering are, thus, life-negating insofar as they promote the nihilism of despair.

The conclusion Nietzsche thus reaches is that any non-nihilisitic value system must embrace the inevitability of suffering, and he advocates the will to power as his solution. The doctrine of the will to power holds that the highest good is power itself, and power just is the “overcoming of resistance” (p. 177). Power is only manifested (as Schopenhauer had already suggested) in the course of its practical, concrete exercise. It is not a “thing,” but rather a process or “activity” (p. 196) that occurs when two forces encounter one another and clash. There is, in this sense, no such thing as potential, unexpressed power; only power actually manifested in the course of active expression. Power becomes manifest only when there is some obstacle to be overcome. Furthermore, any obstacle we encounter must offer some degree of opposition to our efforts. But opposition to our will is also what makes for difficulty, struggle and suffering in life. With resistance, thus, there is always pain and suffering, but without it, there is no possibility for the exercise of will power and the sort of overcoming that makes us feel happy and joyful in our accomplishments. It follows, then, that if we are to value power as our highest value, then we must also value suffering.

By elevating the will to power to the highest of all values, Nietzsche accomplishes a revaluation that he believes satisfies both of the conditions for a meaningful life. First, since power just is the overcoming of obstacles, and since all humans value this sort of overcoming (regardless of the nature of the particular obstacle that they overcome), the will to power represents a goal that is intrinsically valuable. Thus it overcomes nihilism as disorientation. Second, since power is always concretely expressed in this world, it is, by its very nature, something attainable (in varying degrees) in the here-and-now. It is not an illusory, unrealizable goal. This overcomes nihilism as despair.

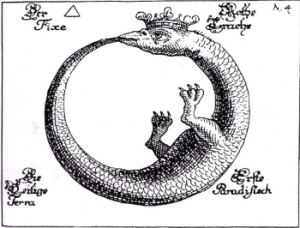

The last two chapters of Reginster’s book address Nietzsche’s doctrine of eternal recurrence and his advocacy of Dionysian wisdom, suggesting that both are integral to the preceding interpretation. Just as the will to power offers an alternative to the belief in God, the eternal recurrence offers an alternative to the Christian ideal of eternal life in heaven. It is an attempt to conceptualize life as active, never ending becoming rather than as a static state of passive being. In this way it encourages us to embrace impermanence, which is at the very heart of the idea of will to power as a process. Finally, with the mythic figure of Dionysus, we find another alternative to Christian ideals. In Christianity, it is the beaten and battered Christ, and his condemnation of suffering, that inspires admiration, while the god Dionysus, on the other hand, represents the life-affirming celebration of destruction, suffering, and change as parts of the creative cycle of nature itself. In these ways, Reginster suggests, both Dionysus and the eternal recurrence are something like Nietzschean myths, offered as alternatives to the traditional Christian myths of God, Christ and heaven. For readers who embrace his revaluation in terms of the will to power, they represent life-affirming, non-nihilistic guidelines for how to live life in the here and now.

The last two chapters of Reginster’s book address Nietzsche’s doctrine of eternal recurrence and his advocacy of Dionysian wisdom, suggesting that both are integral to the preceding interpretation. Just as the will to power offers an alternative to the belief in God, the eternal recurrence offers an alternative to the Christian ideal of eternal life in heaven. It is an attempt to conceptualize life as active, never ending becoming rather than as a static state of passive being. In this way it encourages us to embrace impermanence, which is at the very heart of the idea of will to power as a process. Finally, with the mythic figure of Dionysus, we find another alternative to Christian ideals. In Christianity, it is the beaten and battered Christ, and his condemnation of suffering, that inspires admiration, while the god Dionysus, on the other hand, represents the life-affirming celebration of destruction, suffering, and change as parts of the creative cycle of nature itself. In these ways, Reginster suggests, both Dionysus and the eternal recurrence are something like Nietzschean myths, offered as alternatives to the traditional Christian myths of God, Christ and heaven. For readers who embrace his revaluation in terms of the will to power, they represent life-affirming, non-nihilistic guidelines for how to live life in the here and now.

There is much more argumentative detail in The Affirmation of Life than I have summarized here. Reginster goes to meticulous lengths in building his own position, remaining very diligent in his reconstruction of competing interpretations of the material, and providing plausible counterarguments for why his own reading of Nietzsche is especially consistent and complete. It was a pleasure to follow along with the author’s thinking process, which exhibits an unusual amount of analytic skill and care for the material. My only criticisms of the book have to do with the lack of a concluding chapter and Reginster’s omission of any serious engagement with Heidegger’s major work on Nietzsche.

Given that the arguments in The Affirmation of Life are so intensely detailed and interlocking, it would have been nice if there was final summation of the book’s overall argumentative trajectory. As it is, the book ends rather abruptly, with a short but incomplete two page conclusion tacked on to the last chapter on Dionysian wisdom. I did a lot of underlining as I read through the book for a second time, and once I got to the end of its 268 pages, I had to go back through and reconstruct the overall argument for myself. I hope I got it all right. In any case, it would be helpful if, upon reaching the end of the work the author’s own summation was provided so that a reader like myself could be reassured that he got all of the pieces in the proper order.

The omission of Heidegger is a complaint only because it struck me, once I had finished the book, that there are aspects of his four volume work on Nietzsche that are directly relevant to Reginster’s interpretation. Heidegger, like Reginster, attempts to demonstrate that Nietzsche’s various doctrines – the will to power, the eternal recurrence, and nihilism – all play integral roles in a consistent Nietzschean philosophy. He also claims that the will to power is central to the revaluation of values and that the eternal recurrence is Nietzsche’s way of attempting to think Being as a process of becoming. One of the major – and I think very interesting – differences is Heidegger’s claim that nihilism is not something that can legitimately be “overcome,” since instead of a problem or crisis, nihilism is actually an aspect of Being itself. I am curious as to how Reginster would respond to this Heideggerian reading of Nietzsche.

The omission of Heidegger is a complaint only because it struck me, once I had finished the book, that there are aspects of his four volume work on Nietzsche that are directly relevant to Reginster’s interpretation. Heidegger, like Reginster, attempts to demonstrate that Nietzsche’s various doctrines – the will to power, the eternal recurrence, and nihilism – all play integral roles in a consistent Nietzschean philosophy. He also claims that the will to power is central to the revaluation of values and that the eternal recurrence is Nietzsche’s way of attempting to think Being as a process of becoming. One of the major – and I think very interesting – differences is Heidegger’s claim that nihilism is not something that can legitimately be “overcome,” since instead of a problem or crisis, nihilism is actually an aspect of Being itself. I am curious as to how Reginster would respond to this Heideggerian reading of Nietzsche.

In any case, I highly recommend Bernard Reginster’s The Affirmation of Life: Nietzsche on Overcoming Nihilism to those readers who have a serious interest in Nietzsche, nihilism and who appreciate detailed, scholarly and meticulous argumentation. This is not a book that can be read through quickly or superficially. It is one that requires patience, time and focused attention. It is a difficult book in these ways, but as Reginster himself suggests, difficulty goes along with the overcoming of obstacles, which in turn makes us happy in the expression of our will to power!