File download is hosted on Megaupload

Christopher Newfield’s The Great Mistake: How We Wrecked Public Universities and How We Can Fix Them (2017) should be required reading for anyone who is interested (or contractually obligated to be interested) in the University of North Dakota budget debate. Newfield served on various campus and system wide committees at UCSB and in the University of California System during several rounds of drastic budget cuts in the early 21st century. His experiences collaborating with his colleagues, pouring over the budgets, and interacting with regents, administrators and the public have imparted his scholarship with a hard-won practical edge that both makes it more immediate in impact (this is not a theoretical book), but also demonstrates the conceptual fractures that exist throughout the current conversation about higher education.

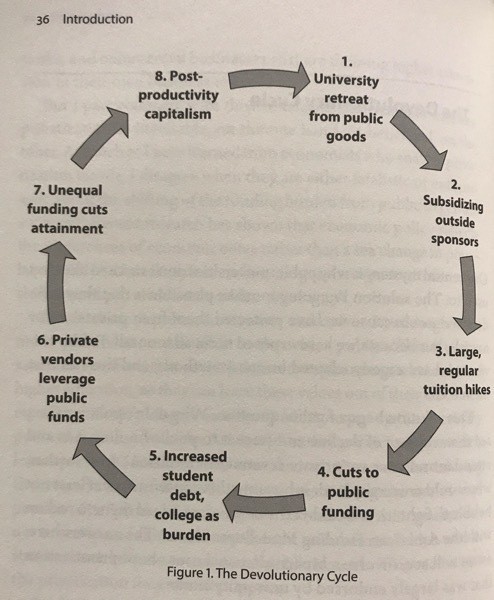

Newfield centers his argument on the broad concept of “privatization” which he used to describe the process whereby public universities turn to private capital, services, and institutions to support their public mission. He explains the process through a six step chart where each step inform the next. It begins with the university retreating from public goods which results in the need to seek outside sponsors and regular tuition hikes. These provide a reason for public funding to be cut, especially during economic downturns, and not restored, increasingly amounts of this deficit shifted to student debts, the growing use of private venders in a quest to do more with less, uneven backfilling across systems where students who would benefit the most from high levels of investment receive the least funding, and a growing maze of arguments based upon “post-productivity capitalism” where credentialing a workforce matters more than training the next generation of leaders.

Newfield claims his book is meant for parents and even students who are struggling to understand why higher education appears to struggle to fulfill its promises, but the book actually speaks to a much wider audience and brings together a much confusing and complicated set of discourses that have all claimed particular insights into recent changes in higher education.

For example, “privatization” serves as a useful way to understand how universities have explicitly retreated from working toward the public good. As Charles Dorn’s recent book has attempted to show, universities have shifted their attention more and more to engaging with the market in ways that range from their emphasis on “work force development” to public-private partnerships seeking to monetize university research. Newfeild add nuance to this kind of privatization, by seeing it as both a cause for the fiscal (and cultural crisis) at the university as well as a result of this crisis and the shift toward a viewing the market as the ultimate arbiter of public good.

Elsewhere in his book, Newfield discuss the breakdown between the desperate need for universities, their administrators, and their supporters in the legislature to make they case to the general public for universities as a public good. He demonstrates the complicated political and cultural context for – to use Stefan Collini’s term – “speaking of universities” in the public sphere. In part, university administrators are stuck between the eroding confidence in public institutions (despite their quiet ubiquity in our everyday life) and growing confidence in “free market” technological solutionism, the potential of commercialization, longstanding (if mostly quietly held) belief that the poor are morally or intellectual deficient, and persistent, misplaced faith in the rising economic tide lifting all ships. These are powerful currents in the public discourse that both shape the views of university administrators (and faculty) as well as the views of the general public to whom any appeal to the public good must be made.

Newfield even engages the conclusions reached by Arum and Roska in their widely read and cited Academically Adrift which argues that in many cases, universities fail to improve fundamental student skills. Newfield shifts the responsibility for these failings from faculty, institutions, or even students to the existing funding models of higher education which tend to support students at private schools or upper tier public institutions with higher levels of funding per student which allows for more intensive teaching practices that emphasize writing, reading, and one-on-one . At UND, for example, funding cuts will lead to larger classes, less teaching support from graduate assistants, and increasing reliance on digitally mediated approaches to instruction and evaluation. While digital tools may serve to bridge in part, Newfield emphasized that, in general, digital solutions have not yet delivered on their promise to make conventional teaching practices obsolete. There will be risks and these risks will both cost money and impact student learning.

Finally, Newfield does take the reader into the weeds of higher education finance with a brilliant little discussion of how sponsored research (predominantly grants) impact the bottom line at universities. Generally speaking, in contemporary academic culture, grants are seen as an important source of income for universities. Despite this, it is well known among administrators, at least, that grants often cost the university money despite the fact that most grants bring with them funds for the indirect cost designed to support the cost of administering the grant, the ongoing investments in research infrastructure, and the longterm cost of the grant in depreciation of equipment and maintenance. In general, Newfield demonstrates, the cost of research exceeds the funds provided by most major federal grants and this gap is covered by other funds. This is intentional as the federal government, in particular, hoped that by limiting the funds not directly focused on research, they will force universities to be more efficient. Instead, it has pushed universities to do research at a loss and continue to go after grants – year after year with growing intensity – to feed the research beast and like a Ponzi scheme director who is increasingly worried about investors making a call, universities must continue to push for grants or, more frequently, seek to privatize support for public research through partnerships with companies, moving tuition dollars to cover research losses, and endowments. These moves, in turn, compromise research for the public good by making it increasingly beholden to private interests (via corporate partnerships and fund raising).

Newfield’s book is sophisticated, smart, and very readable, and unlike many books that seek to understand and resist the current climate in higher education, Newfield’s book shows all the signs of adding persistent value to the ongoing conversation. Go and get it.