File download is hosted on Megaupload

Dusting ‘Em Off is a rotating, free-form feature that revisits a classic album, film, or moment in pop-culture history. This week, Wren Graves looks at how the iconic German band stamped out false impressions of their music and politics.

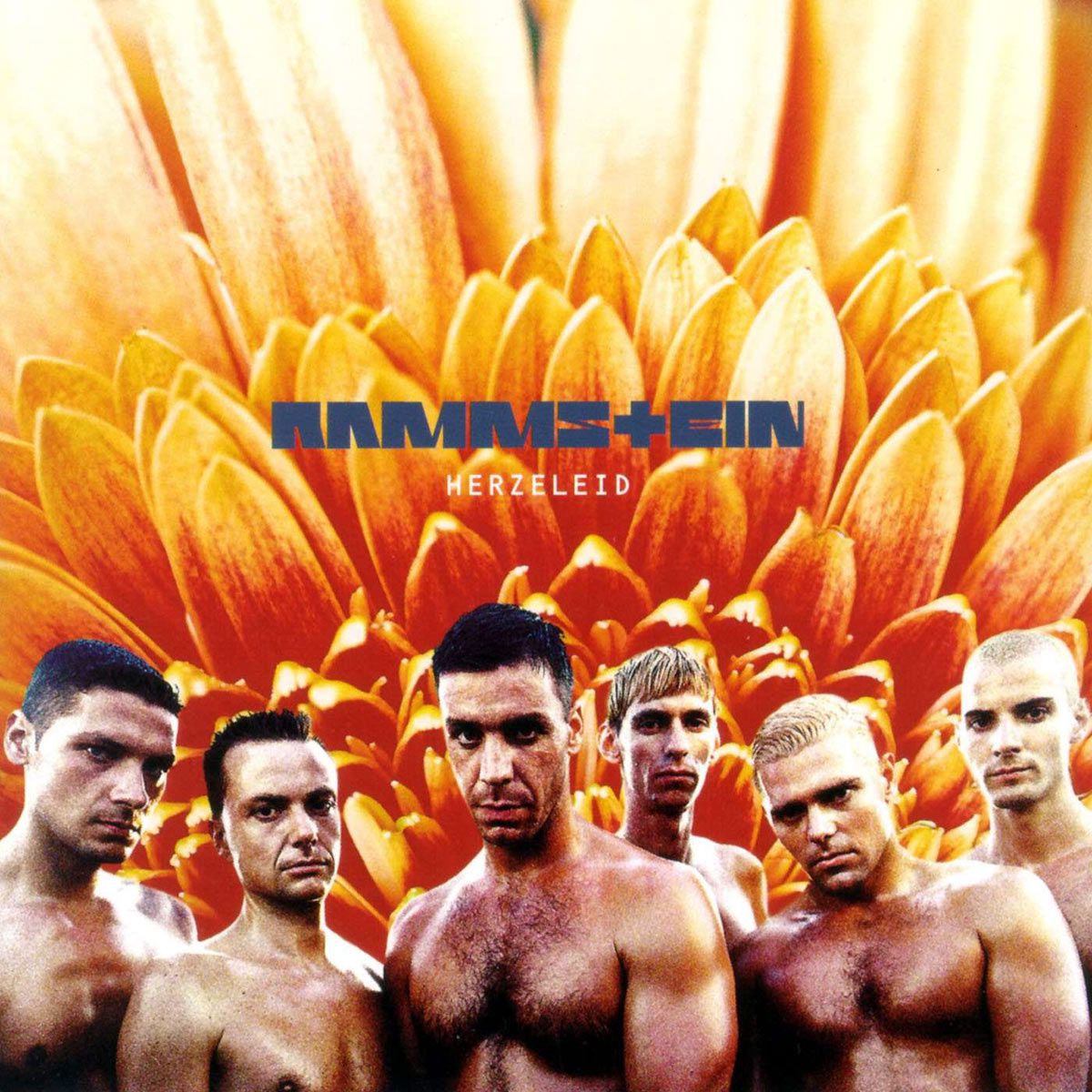

This is a story about communication — about what gets lost in translation and how the intended message can be so different from the one received. It’s about a group of provocateurs who tried to stay out of politics, but got caught up in the pressing political arguments of their time. When Rammstein released their second album, Sehnsucht (often translated as Longing), they were already well known in Germany; their first album, Herzeleid (Heartache) was on the German charts for 102 weeks. Critics were so excited by this aggressive new blend of American heavy metal and Continental electronica that they had to invent a new genre to describe it: “Neue Deutche Harte,” the New German Hardness.

Rammstein means “battering stone,” but that’s not the whole story. The band loves homophones, those slippery groups of words that have similar pronunciations but different meanings. And while Rammstein may be spelled like battering stone, it sounds exactly like Ramstein, the site of the 1988 Ramstein Air Show disaster. Held at an American Air Force Base in West Germany, 70 people were killed and hundreds more injured when two Italian pilots collided in mid-air and crashed into the crowd below. Early on, the band even toured under the name Ramstein-Flugschau (Ramstein Airshow). And so you hear Rammstein, and you’re meant to think of a battering stone, but also a fiery collision of American militarism and European aesthetics. There’s lots of this double-talk in the music, which made them a somewhat unlikely candidate for English-language crossover success.

But Rammstein has a flair for spectacles — costumes and pyrotechnics — that translates into every language. They give fire-breathing live performances, both figuratively and literally. During renditions of their first single off Sehnsucht, “Engel” (“Angel”), lead singer Till Lindermann would wear a pair of flaming angel wings while sparks shot out of Christoph Schneider’s drumsticks. Of course, all the fireworks in the world won’t sell a dull song, and “Engel” is anything but. It’s a study in contrasts: an angelic soprano paired with a brimstone baritone and thundering guitars supported by lonesome whistles and shimmering synths.

The lyrics reflect on the afterlife, which the characters in the song seem to wish didn’t exist. The first three lines of the hook are sung by the German pop star Bobo. She coos: “First if the clouds have gone to sleep/ You can see us in the sky/ We are afraid and alone.” To close the couplet, Lindermann roars the final line: “God knows I don’t want to be an angel!”

But it was with their second American single, “Du hast”, that Rammstein crossed over from heavy metal stations to the much more popular alternative radio. The song depends on a bit of subtle word play that gets lost in translation. “Du hast,” means “You have,” but the pronunciation is indistinguishable from “Du hasst,” meaning “You hate.” It’s a recollection of a conversation at the end of a romantic relationship. The partner asks, “You have me?” As in, will you have me — will you keep me, will you marry me? But also the second meaning — do you hate me? Till Lindermann sings his response, “And I did not answer.”

The guitar is relentless, and the drums keep up a quick military march. A choir adds a touch of the epic, and the synthesizers deployed by Christian “Flake” Lorenz wouldn’t sound out of place in dance halls from Kingston to Kiev.

For the live show, Lindermann wielded a flaming bow and arrow like a cupid from hell.

That performance was taken from their 1998 American tour, which I attended when it stopped in Madison, Wisconsin. I was in middle school, and at the time I had a friendly relationship with my German teacher, a diminutive German immigrant with a thick accent, glasses, and short-cropped, gray hair, whose last name I’ve forgotten, but who encouraged us to skip it altogether and just call her Frau. The day of the Rammstein show, I was excited to tell Frau that I was going to see a German band.

She smiled up at me, eyes sparkling. “Oh?” she said in her accented English, “And what band is that?”

“Rammstein,” I replied.

Her smile slipped and was replaced with a look of horror. “Rammstein?” she said. “But they are Nazis! They like Adolf Hitler!” And she eyed me warily, afraid that I supported Hitler, too.

That night at the show, as Lindermann fired flaming arrows over the crowd, I watched with a mixture of awe and discomfort. Was Frau right? Were they really Nazis?

In retrospect, the trouble started with Rammstein’s album cover for Herzeleid. The six band members are presented shirtless, with hair that is closely cropped or shaved. Frankly, they look a bit like skinheads, and many people wondered if they were.

White nationalists were often in the headlines in Germany at that time. A few years earlier in 1992, the German Ministry of the Interior banned half a dozen far-right and neo-Nazi political parties (freedom of speech is much more restricted in Germany than America) with names such as “German Alternative,” “National Front,” and “National Opposition.” In 1995, the same year that Herzeleid became a sensation, Germany’s Constitutional Court banned another far-right group, the Free German Worker’s Party, whose platform was anti-immigrant and pro-white.

Rumors began linking Rammstein to far-right politics, Nazism, and white nationalism. A 1998 Wall Street Journal article collected some of the harshest criticism: “If there was still a Third Reich, would a band like Rammstein appear at the 35th Nazi Party congress?” asked a Dresden entertainment magazine before a recent concert there. The Schweriner Volkszeitung, a German newspaper, observed that Mr. Lindemann rolls his “R”s like Hitler.”

Rammstein called this stuff “nonsense.” But the accusations followed the band through their second album, Sehnsucht, and reached America at the same time they did.

Rammstein denied these rumors to the American press, and complained about the Herzeleid cover controversy. “It’s all been so silly,” Lorenz told Hit Parader. “That was just a photo of us — not a political statement!” Lorenz blamed the hubbub on the German media. “We’ve never written a political song in our lives,” Flake said, “and we probably never will.”

This is not to say that Rammstein shied away from controversy; on Sehnsucht, they violate many taboos within intimate character studies. Not one, but two songs are devoted to incest: “Tier” (“Animal”) and “Spiel mit mir” (“Play with me”). “Tier” tells the tale of a father raping his daughter. The song is upbeat and anxious, with a guitar riff like a thumping heartbeat.

The album version of “Spiel mit mir” starts with a kind of creepy nursery rhyme about two brothers who “share a room and a bed.” One urges the other, “Play with me!” Slow and sour, it works by combining a child’s innocence with an adult’s gag reflex.

In the video below, Lindermann rises out of the stage dressed like a cross between the Terminator robot and King Kong. This isn’t Metallica in a t-shirt and jeans; this is a lavish German opera.

The outfits and the incest bring me to a theory about Rammstein — a theory I can’t prove. From the beginning, I think Rammstein wanted to be controversial, but I think they wanted to be controversial in a more traditional way. I think they wanted to follow in the footsteps of Kiss or Marilyn Manson — to dress up in fun costumes and shock some parents.

Rammstein were able to do a bit of this on their 1998 American tour. “Buch dich” (“Bend down”) features familiar metal tropes of domination and humiliation. Rammstein places it in the context of man-on-man anal sex. “Your face means nothing to me/ Bend down!” During live performances, keyboardist “Flake” Lorenz puts on a mask and ball-gag while Lindermann graphically simulates having sex with him. The act even involves a squirting dildo, and in 1999, it got Lindermann and Lorenz arrested and thrown in jail for a night in Worcester, Massachusetts. (When it comes to sex and freedom of expression, Germany is more free than the United States.)

This is a band that, for its whole career, had appeared in newspaper articles next to labels like “neo-Nazi.” It must’ve been a relief to appear next to friendlier words, like “outrageous antics” and “anal sex.” Rammstein were closer than ever to achieving their dream of being an apolitical rock band. And they might have succeeded, too, if not for one of their fans.

Eric Harris liked Rammstein enough to wear their shirt for his 11th grade photo. An admirer of German culture, Harris often started his journal entries with “Wie Gehts,” which translates as “How are you?” or “How’s it going?” He listened to other German industrial bands, especially KMFDM, and tried to get his friend Dylan Klebold into the music, too; he scribbled “Rammstein” in one of Klebold’s journals.

Harris wrote admiring school papers about Hitler, calling him evil but also saying, “Hitler was the best leader Germany had.” In his own journal, he wrote the name of a song by Rammstein, “Weisses Feisch”. Beneath that, he wrote “perfect / song / for / me.” The entry that follows: “Well folks, today was a very important day … we went downtown and purchased the following; a double barrel 12ga. shotgun, a pump action 12ga. shotgun, a 9mm carbine, 250 9mm rounds…” the list goes on. Here are the first few lyrics of “Weisses Fleisch” in English: “You, in the schoolyard/ I am ready to kill/ And no one here knows/ Of my loneliness.”

On April 20th (Hitler’s birthday) of 1999, Harris and Klebold entered the Columbine High School cafeteria and started shooting. They massacred 13 people — 11 students and two teachers — and injured an additional 24, before turning their weapons on themselves.

As America attempted to understand what had happened and why, the name Rammstein kept popping up.

Briefly: no, Rammstein didn’t incite the Columbine shooting. Rammstein have millions of fans who have never shot up a school, and if the band had never existed, Harris would surely have been listening to somebody else. I want to get that out of the way and focus on Rammstein, because I think what happens next is instructive. The Columbine massacre is an unofficial bookend in their career — the end of the Sehnsucht era, the start of something new.

Rammstein never wanted to be political. Perhaps it didn’t interest them. Perhaps they were afraid of alienating some of their fans. But after years of refusing to define their own politics, they kept getting defined by others. We’re now coming to a key moment: Offstage, where fans can’t see, Rammstein is going to make a choice.

The next period begins with a song that fans knows well: A single off third album Mutter, “Links 2 3 4”.

“They want my heart on the right place,” Lindermann sings, in reference to right-wing extremism. “But if I look down on me/ Then it beats left!” The music video makes it even more explicit: communist ants working together to defend themselves from Nazi beetles. At the end of the video, ants crawl over a dead right hand, symbolizing triumph over the far right.

Now, what Germany considers left and right on the political spectrum is undoubtedly different than how we talk about it in the US. The point isn’t that it’s somehow heroic to announce how you like to vote; in fact, you could make the case that Rammstein were cowardly for not disassociating from extremists earlier. But they did it, and it presaged a broadening of their sound; fewer intimate character studies, more big ideas, the philosophies of “Amerika” and “Dalai Lama”. That comes later; right now we’re interested in the moment before.

Before all that, right after the Columbine shooting, when they were still struggling to keep out of politics, they released a woefully bland public statement: “The members of Rammstein express their condolences and sympathy to all affected by the recent tragic events in Denver. They wish to make it clear that they have no lyrical content or political beliefs that could have possibly influenced such behavior. Additionally, members of Rammstein have children of their own, in whom they continually strive to instill healthy and non-violent values.”

I am particularly fascinated by that second sentence, where they “wish to make it clear” that their lyrics and their politics had nothing to do with the ideas behind Columbine. But how would Harris and Klebold have known that? What had Rammstein ever done to make it clear?

Who knows what the band thought about afterwards, offstage, outside the public eye. We know the end result: Rammstein decided to write a song so that it would be clear in the future.

There are many lessons here for us, as America grapples with a resurgence of right-wing white nationalism of our own. We see how a well-intentioned media can get a story wrong; the importance of defining yourself before others define you; and how easy it is to send a message you don’t mean. There’s also hope, because Rammstein came out of the experience as a better all-around rock band. Sehnsucht is a great record. It took Rammstein out of Germany and onto the world stage. But the experience of promoting Sehnsucht changed Rammstein, so that afterwards they couldn’t just write another Sehnsucht; they had to make something new.