File download is hosted on Megaupload

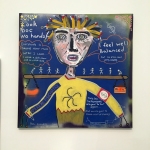

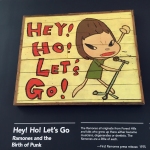

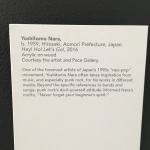

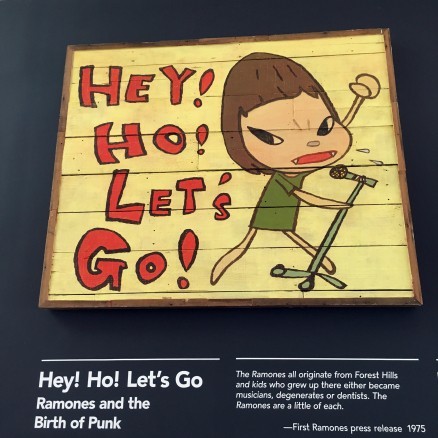

2016 art by Yoshitomo Nara.

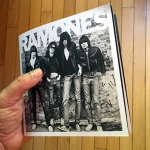

The Ramones released their eponymous album on April 23, 1976, on Sire Records, and on July 4 of that same year played their first non-US show at the Roundhouse in London, igniting the Punk fuse under British bands such as the Damned and the Clash, some of whose members were in the crowd that night. It was a Punk Independence Day in the UK ushered in by four burnouts from Forest Hills, Queens.

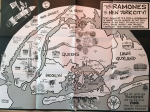

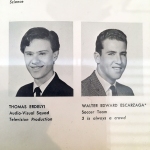

To celebrate Punk’s 40th birthday, the Queens Museum is hosting a Ramones retrospective exhibition, which will close on July 31, re-opening at the Grammy Museum in Los Angeles on September 16. What sets this exhibition apart from others of its kind is the fact that it ties Punk to place, namely Forest Hills, and contains ephemera about (or belonging to) the band members and their friends and families before the Ramones formed. The concept of Punk-and-place is not new to this blog, and you can read more about that here.

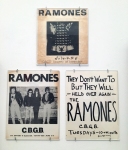

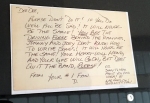

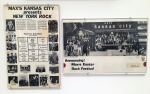

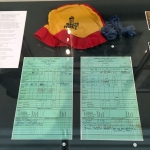

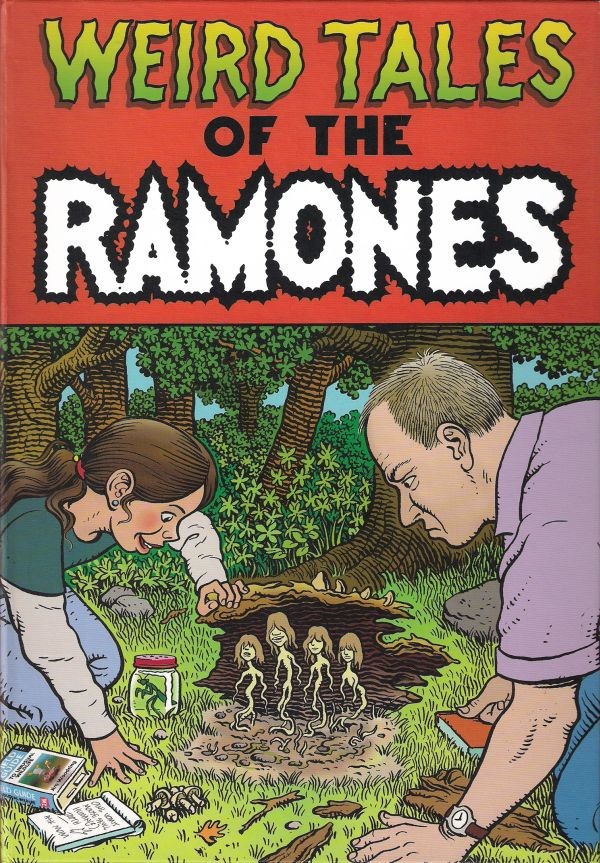

The exhibition places the band inside the context of the fledgling Punk scene in New York City with posters and handbills from CBGB and Max’s Kansas City, and photos of Blondie, Wayne County, Iggy Pop, and others. There are handwritten setlists and lyrics, art made by the band members and their fans, fan letters, original album art, original concert merch, backstage passes. Artifacts of the band include gear and clothing, as well as elements of when the Ramones were “becoming”, including an original demo tape and press kit. Visitors tour three galleries arranged chronologically, encountering Joey’s “Gabba Gabba Hey” sign and memorabilia from the film Freaks and later from Rock and Roll High School.

We see the Ramones invent themselves and their sound, creating not just a Punk phenomenon, but a pop culture one as well, becoming part of the American vernacular as they played over 2,500 shows. Not only do we see the transformation, we hear it as well, as Ramones tunes invite guests in to learn about the origins and growth of a legendary band. Through the Ramones’ artifacts and an attempt to place the band in first a local context, then in the context of the Punk scene, and then on their own terms as a global juggernaut, the exhibition attempts to explain a legend through the sum of its interconnected parts. We don’t quite get a feel for the men themselves through what has been preserved. What we do get, however, is a look at the band-as-virus, spreading Punk wherever it touched down. It’s the creation and circulation of a blueprint. Or perhaps a ‘zine.

The final gallery is entered through a glass door installed in a vain attempt to dampen the sound of a Ramones concert film played on continuous loop. In the back of the room, placed almost as an afterthought, is a case containing the Ramones’ lifetime achievement Grammy and Rock and Roll Hall of Fame statues. This almost hidden placement is clever, though, reminding us that the band was not about achievement; it never was, instead focusing on communication through music to as many people as possible. Such is Punk rock.

When I visited, about eight other people were seated in chairs, listening to the concert footage and smiling. And it marked the first time that I’ve ever seen EVERY SINGLE PERSON smiling in a museum exhibit, without exception. The exhibit walked the nostalgic line to be sure, but did its best to address the Ramones and Punk generally on their own terms, a creative force.

Below is a gallery of images I shot while touring the exhibit. Click on an image to learn more about it, and to enlarge it.

-Andrew Reinhard, Punk Archaeology