File download is hosted on Megaupload

It seems strange in 2014, when record collectors have picked over everything from pre-Revolutionary Russian vocal 78s to Vietnamese soul, that the musical history of Spain is still largely unknown internationally.

After all, some 800,000 British people live in Spain and millions more come to the country every year. What’s more, the musical histories of France, Germany and Italy – countries that many British people once turned their noses up musically – have all been mined to considerable acclaim, turning up wonders of Yé Yé, Krautrock and giallo respectively.

So why not Spain? There is, of course, the country’s troubled recent history: while Britain basked in the summer of love Spain was living under a military dictatorship that had no great love for pop music and would censor records that didn’t meet with its nationalist, pro-Catholic views.

These are hardly the ideal situations for the cultivation of a thriving pop scene and it was telling that La Movida Madrileña (the countercultural movement that took place mainly in Madrid after Franco’s death in 1975) saw an explosion in popular music that continues to vibrate in Spain to this day, courtesy of the likes of Alaska and Radio Futura.

But to say the Franco dictatorship laid waste to Spanish popular musical culture is a dramatic oversimplification. After all, Fela Kuti flourished despite opposition from the Nigerian military governments of the 70s and 80s and in 60s Spain the influence of tourism had helped to bring a certain freedom to the country.

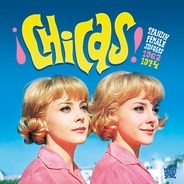

“We think that a terrible dictator is capable of annulling anything. But the Franco dictatorship of the 40s and 50s was very different from that of the 60s and 70s, when there were corrective factors like tourism coming in, bringing a bit of liberty,” says Vicente Fabuel, a renowned Spanish record collector, record shop owner and album compiler, whose ¡Chicas! Spanish Female Singers 1962 – 74 compilation for Vampisoul would prove my way into the wonderful expanses of Spanish pop music history.

“Even without this tourism,” he adds, “rock and pop was a small thing in media terms and the censor was incapable of controlling it al. In the 60s 200 different records would come out and there were three censors in their small room trying to listen to everything. I am sure they didn’t bother to listen to lots of things. They were there, drinking wine, and would occasionally censor something.”

There were other reasons, too, that the censors might miss the 24 tracks Fabuel has compiled on his excellent Chicas compilation (volume 2 of which is currently in production): the songs here were largely B sides on records that would sell in their hundreds, not thousands. As such, they were generally ignored by both record companies and radio.

“They were small parts of liberty,” Fabuel explains. “It was as if the record company said, ‘OK on the B side put out what you want. It won’t get on the radio.’”

This liberty is found not just in the songs’ progressive lyrical feel – Pili I Mili’s Un Chico Moderno, for example, expresses the singers’ dissatisfaction with the male race in ways that the patriarchal Spanish society of the time would have probably found quite unsettling, while Sonia’s cover of The Rolling Stones Get Off My Cloud is fantastically dismissive of the world in general – but also in musical terms, with arrangements that add a distinctly Iberian twist to what was being produced by the British and American pop industries of the time.

Key to this is the work of (now defunct) Barcelona label Discos Belter, which Fabuel describes in the liner notes as “fascinating, mysterious and immense”.

Eight tracks originally released on Belter feature on the compilation, with the pick of the bunch probably Marisa Medina’s stomping No Te Acuerdas de Mí, which typifies Belter’s “sharp bass, diabolic percussion breaks, scat choruses and precise horn arrangements” according to Fabuel. As a description, it is pretty spot on, with the result coming over like an Iberian Motown, full of Latin drama, sweaty funk and intricate arrangements.

This comparison is made explicit by another Belter track, this time a cover of The Four Tops’ Reach Out I’ll Be There by Los Stop, which gives the Motown hit a furious female power, courtesy of singer Cristina. Closing the album, Lia Uyá (another Belter artist) arguably betters the original on her cover of Three Dog Night’s Liar (here translated as Mientes and given a breakneck drama).

Fabuel says the Belter story is “a mystery”, with little known of the creative teams at the label. However, he believes that the Belter sound came from the label using a small group of musicians when recording, much as Motown and Stax did in the US.

It’s not all Belter making the running on the album, though, nor is the release dominated by covers. Among the original tracks there are two startlingly unique numbers: La Máquina Infernal by Vainica Doble, which marries classical Spanish singing with 60s psychedelia, while Sevillian singer Encarnita Polo showcases her pioneering work on the flamenco pop movement with a cover of – what else? – traditional Jewish folk song Hava Naguila. Both songs are quite unlike anything I’d heard before.

Fabuel says that Vainica Doble – Mari Carmen Santoja and Gloria van Aerssen, “princesses of irony, imagination and tenderness” – represent “the peak of Spanish musical culture” and should be counted among the great European pop groups of the last 50 years. Their Heliotropo album – from which La Máquina Infernal is taken – comes particularly recommended.

Less original – but no less worthwhile – is Por Eso Vuelve, Por Favor by Argentinian group Los Tíos Queridos, a fabulous soul number whose drum breaks and roaring Hammond sound like they should be lighting up Wigan Casino rather than Franco’s Spain; and Contrapunto, by Madrid’s Los Que Vivimos, a stirring psychedelic number which has the looming menace of the best of that genre.

Meanwhile, for those with a strong stomach Love, Love, Love by Los Hippy-Loyas (a play on words on “gillipollas” – dickhead) is definitely worth a listen. The song is taken from the 1969 satirical film Un Día al Año ser Hippy no Hace Daño and it shows, with nonsense lyrics about cigarettes, love and money, all sung in heavily accented Spanish.

It would be nonsense, were it not for the brilliantly funky backing – again from the Belter factory – that features a wonderfully rousing piano and horn chorus. The results, as Fabuel explains, are “indescribable”.

“It was led by people who tried to joke about young music,” Fabuel explains of the song. “But they invited musicians who knew how to play and who loved rock and pop. So the song transcended the ironic intentions.”

Love, Love Love is typical of ¡Chicas!, then, not so much for its sound as for the way it stamps an Iberian identity on the Anglo American pop template, giving the genre just about the respect it deserves without being scared of creating something new that snobbish music fans in New York or London might see as “unauthentic” (whatever that means).

As such, Chicas is an essential album for open musical minds. The compilation may only skim the surface of a bubbling, if unlikely, pop underground – Fabuel is currently compiling not just Chicas 2 but also an equivalent compilation of male singers and a “Spanish Nuggets” – but it is enough to raise the interest in any open-minded listener.

And while Spanish pop of the 60s may prove little more than a footnote to foreign listeners, you could have said the same about Serge Gainsbourg 20 years ago and his reputation is now close to untouchable.

“How would I sell Spanish pop history to a foreign audience?” Fabuel concludes. “I would say, with Spain, in these records there is a foreign influence from the big rock and pop acts of the era. But there is also an aportación personal – a personal input that comes from our culture and not just from flamenco.

“There is an aportación personal indiscutible. That can be enriching and surprising.”