File download is hosted on Megaupload

When it comes to the influence of the arts on everyday life, it can seem like our reality derives far more from Jeff Koons’ “augmented banality” than from the Fluxus movement’s playful experiments with chance operations, conceptual rigor, and improvisatory performance. But perhaps in a Jeff Koons world, these are precisely the qualities we need. Mainly based in New York, and “taking shape around 1959,” notes the University of Iowa’s Fluxus: A Field Guide, “the international cohort of artists known as Fluxus experimented with—or better yet between—poetry, theater, music, and the visual arts.” Big names like John Cage and Yoko Ono might give the uninitiated a sense of what the 60s art movement was all about. An “interdisciplinary aesthetic,” writes Ubuweb, that “brings together influences as diverse as Zen, science, and daily life and puts them to poetic use.”

Of course, there’s more to it than that… but Fluxus artists keep us wondering what that might be, suggesting that ordinary experience and the stuff of everyday life provide all the material we need. Japanese artist Mieko Shiomi describes Fluxus as a “pragmatic consciousness” that makes us “see things differently in everyday life after performing or seeing Fluxus works.”

The definitions of Fluxus, you might notice, can begin to sound a bit circular, maybe because they are entirely beside the point. George Maciunas, who named and co-founded the movement, called Fluxus “a way of doing things.” He called it a number of other things as well.

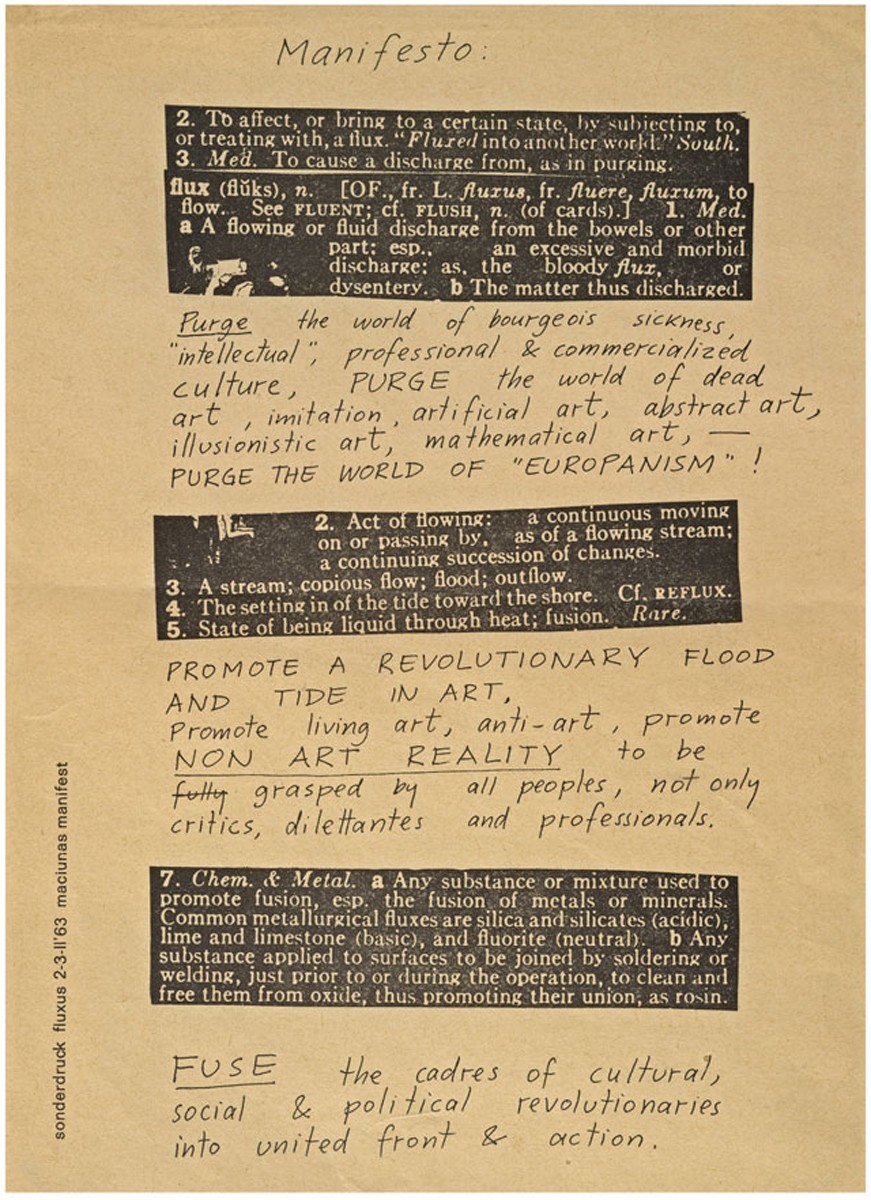

Maciunas’ 1963 “Fluxus Manifesto” makes all the right manifesto moves, paraphrasing Tristan Tzara’s “Dada Manifesto” in its promise to “purge the world of bourgeois sickness, ‘intellectual,’ professional & commercialized culture,” and so on. He begins with a dictionary definition of Fluxus, involving the symptoms of dysentery, and “the matter just discharged.” But the art of Fluxus, aiming at a “non art reality,” seems mild-mannered by contrast with this ironic bluster.

Though it could also be dangerous at times, Fluxus was always a form of play, often seemingly contentless, as in Nam June Paik’s “Zen for Film,” a silent, eight-minute film almost entirely composed of a fuzzy white screen or, in the most notorious example, John Cage’s “musical” composition, 4.33.

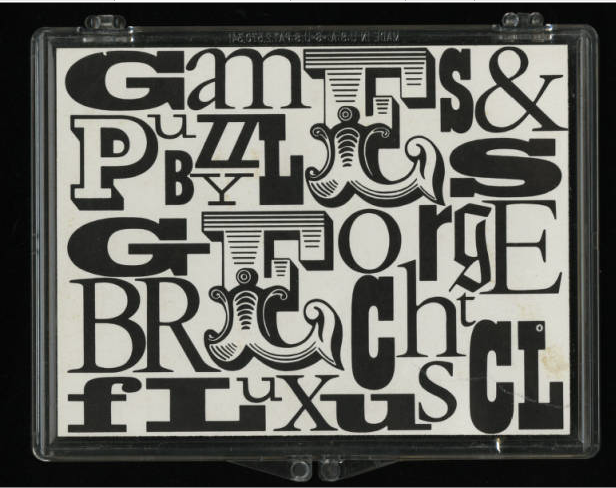

Fluxus has become so closely associated with the musical experiments and performance art of Cage and Ono that the centrality of poetry and the visual arts to the movement can go unremarked. Maciunas himself was a highly skilled graphic artist and an aspiring bourgeois proprietor: he first sought to turn Fluxus into a commercial corporation and designed a number of products such as chess sets, posters, and a wooden box filled with assemblages of small art objects created by his fellow Fluxus artists. He later admitted, “no one was buying it.” Of course, plenty of people did, just not in a way that returned on his sizable cash investment. See an “unboxing” of Maciunas’ Flux Box 2, above and try not to think of Wes Anderson.

Like their Dada forebears, Fluxus artists worked in every medium. At the University of Iowa Library’s Fluxus Digital Collection, you can find visual art by Maciunas and his colleagues, like Joseph Beuy’s “Fluxus West” postcard, further up, George Brecht’s Fluxus Games and Puzzles below it, and A-Yo’s “Finger Box,” above. At Monoskop, you’ll find links to more art, film, music, and books by and about artists like Yoko Ono and Fluxus poet Dick Higgens.