File download is hosted on Megaupload

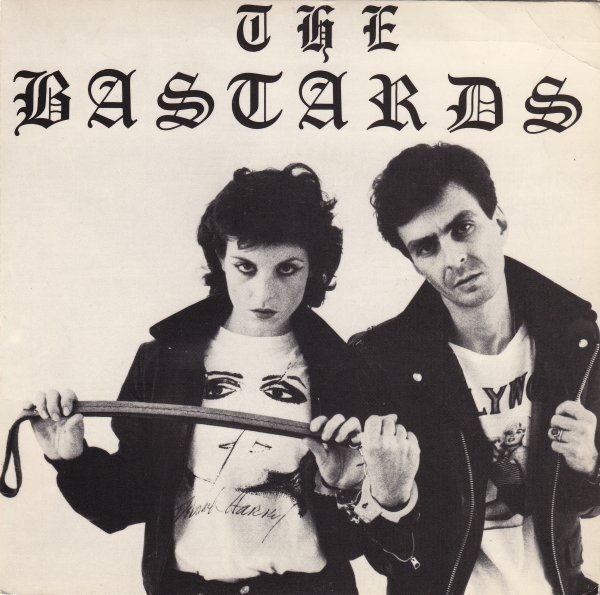

Photos by Lenny Gilmore

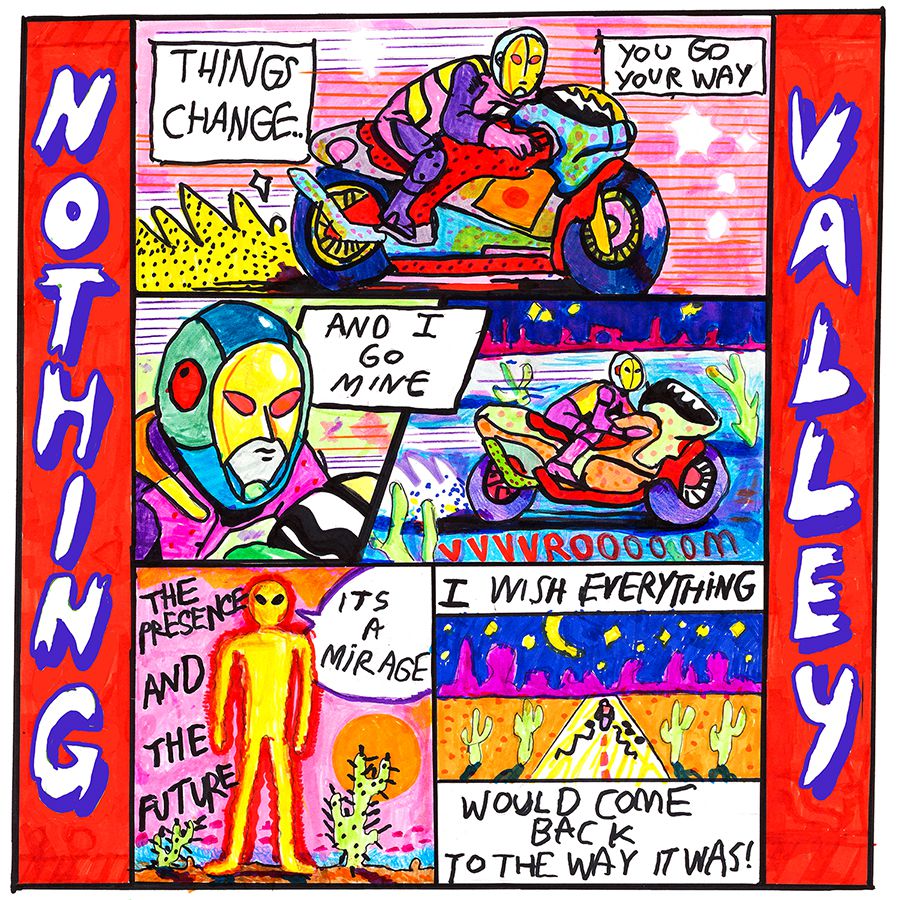

On the massive “Twin Looking Motherfucker”, Chicago quartet Melkbelly push and pull, burn and glow, start and stop. The guitars and bass sound like steel-winged birds flying in formation, each beat a new concussive flap. The drums heave with a distorted burn, never leaving space for a single breath. The vocals tear apart into split personalities, at times pensive and quiet and at others shredding vocal chords. There’s a remarkably taut feeling to that song and the entirety of their debut album, Nothing Valley. But when a husband and wife, his brother, and a jazz-educated, punk-loving drummer get together, that kind of tightly woven chemistry seems second nature.

In 2014, guitarist/vocalist Miranda Winters, her husband/guitarist Bart Winters, his brother/bassist Liam Winters, and drummer James Wetzel came together formally as Melkbelly after circling in various collaborative formations on other projects. The result was incendiary, a noise rock fusion of far-ranging influences, instrumental aggression, and passionate vocals that quickly caught attention throughout Chicago’s DIY scene and live venues. Their Pennsylvania EP released that year only bolstered the reputation, but they spent the following three years proving their strength onstage and sifting out new material.

Throughout that time, the four musicians pushed each other, learned, and grew, always relying on their close-knit relationships as a ballast behind the frenetic, bombastic wizardry of their music. That duality pays dividends on Nothing Valley, an album equally comfortable in lingering tones as it is toothy screams, classic hooks, and decimated noise. A lot has changed since 2014 — in the band’s sound, their inspiration, in Chicago’s scene — but the constancy of their powerful bonds keeps the band deeply rooted and ready to explore even the farthest-flung sonic landscapes.

_________________________________________________________

DIY CHICAGO AND THE POWER OF LIGHTNING BOLT

Miranda Winters (MW): The music scene in Chicago is just so incredibly diverse and so interesting, and everybody just seems so excited about it. There’s this really positive energy, and that’s never, ever changed.

James Wetzel (JW): I think Chicago is changing a lot, though. Places don’t last a long time, so there always feels like there is a level of newness to it.

MW: Yeah, and the local music scene is accepting because of its size. I think that there are a lot more opportunities for DIY spaces experimenting, much like the way that it was in New York at one point, or even on the West Coast. There’s always house shows or spaces that are popping up here. I have bands that I’ve loved since I moved here 10 years ago, and then I’ll see a band that I’ll fall in love with that started a month ago.

JW: We actually met at a secret Lightning Bolt show. My band at the time was opening for that show, and Miranda and Bart [Winters, guitarist] came out to see it. We connected then and started to listen to each other’s music more and got excited about collaborating and sharing a space together. We were both huge fans of Lightning Bolt, and we both have had bands that sound like them.

_________________________________________________________

ON HOW TO BE GROSS AND CUTE

MW: We wanted to have a name that was sort of gross but also a little bit cute! I think we all have a pretty good sense of humor, and it shows up sometimes in the lyrics and often when we’re playing live. We wanted to sound a little gross and a little bit off-putting, but we also didn’t want to take ourselves too seriously.

JW: I like the way it sounds, phonetically. It was the one name that stuck for all those reasons. I think there’s a nice duality to it. I typically don’t think too much about band names as being informative or indicative of something larger, but I do think it works in this case. Our sound is really cute, with all the catchy melodies, but it’s wrapped up in a ball of distortion. That’s a big part of our sound. There was also a point in time where Miranda mentioned it as slang used in her ballet class as a kid, and I thought that was kind of funny. It felt like we were bringing an ancient word back to life.

MW: I was always really fighting to be up at pointe in ballet a lot earlier than was allowed. And the instructor would tell us that your back does a certain thing when you’re really young, and it sticks your stomach out. She said you have a “melkbelly.”

_________________________________________________________

ON BEING UNDERSTOOD AND GETTING COMFORTABLE

JW: To a certain extent, people understood what we were doing on our EP [2014’s Pennsylvania] — but only as much as we sort of did. We made that album really quickly and went through the process of really learning how to write things together, as a group. It was largely based off of songs Miranda would bring in, and we’d work to bring together noise and pop into rock songs. I think people grabbed onto that. We saw it as a gateway, and now our sound feels a little bit more comfortable all these years later.

MW: We probably learned along with everyone else what exactly we were doing or at least how to vocalize it. I think it was more of an internalized thing. Going into that EP, we couldn’t really grasp onto anything, but recording it and playing those songs helped us figure it all out. You can feel the reaction from the crowd when you’re playing a song live, and it does push you or pull you one way or the other when you’re writing or editing the next song.

_________________________________________________________

FAMILY MATTERS

MW: If you had asked me maybe four years ago, I don’t think I would have guessed how close I am to everyone in the band today. I think learning to be that close and trusting other people has definitely altered the way that I make music. While my music was once this really intimate and solo thing, I’m now much more comfortable, and I almost rely on having their brain and skills I can pull from.

JW: We’ve definitely grown really close. I only met all these guys when we started the band, but it’s become more than just a band to me. We all live in the same neighborhood. We’re texting each other all the time. We are a family in a lot of ways. They’re literally family. [Laughs]

MW: Before Melkbelly, I was in a handful of pretty classic rock bands, always with four or five people that were friends. It inevitably would fall apart because there was all of this drama. But when you know that it extends into every place of your life, it affects your interactions. I always used to say I wanted to live in a commune. I couldn’t survive in a commune — there’s lots of stuff I’d complain about [laughs] — but we have set it up so that when we aren’t practicing, we’re probably hanging out, and when we’re not playing one of our own shows, we’re together seeing someone else play a show.

JW: People’s lives get pulled in different directions, but we’re all pulled in the same direction. Playing with someone and developing new chemistry with them can be difficult, but Melkbelly is this bigger thing, and it’s comforting knowing that nobody is really going anywhere. Musically-speaking, I’m trying to harness a lot of the maybe freer, more expressive musical energy that I developed through playing jazz and to weave it into this three-person unit. But now we’ve got a dialogue going that’s been really helpful from all of our perspectives. As individuals, as musicians, really developing that collective voice — what you hear is Melkbelly.

MW: It’s pretty necessary to have that trust. If you’re playing music with somebody, you’re going to know whether or not you like what it is that they’re doing. But it’s important to be comfortable in articulating what you’re hearing and how it could change, but also knowing that the other person that you’re working with is intuitive enough about the music that they’re making.

JW: It can be hard. You might feel more hesitant to say how you really feel if it’s a friend and you don’t want to offend them. With Melkbelly, I’ve always been able to say upfront if I don’t like something or if I’m really passionate about something, knowing that they’ll see that and take it seriously. When we write songs, Miranda comes in with the structure and we pitch different ideas on how to tweak it and make it more of our own thing, trusting each other’s voice.

MW: It can be kind of easy to get selfish when you’re making music and focus on your part. But when you’re working with people that you really care about, you make music that you really care about and you want every little bit to sound the best it possibly can.

JW: It’s not always easy! It’s not all sugar-coated. Some of the most meaningful conversations are the hardest ones to have, but there’s a trust and love that is irreplaceable.

_________________________________________________________

VAN LIFE

JW: Our musical taste is diverse, which makes the rotation of music when we’re living in the van together on tours very interesting. We’re always learning about different stuff.

MW: The unusual things that you wouldn’t expect us to be listening to come from James. He listens to the weirdest stuff.

JW: [Laughs] Sometimes I don’t even know what I’m listening to! I put things on that other members of the band would appreciate, everything from Peter Brötzmann and Sun Ra to Ethiopian music.

MW: I didn’t mean to call you out like that, James! [Laughs] When we’re in the van, we’ll create a playlist based on whatever it is we’re going through or coming from. We do this thing where we’ll start a playlist and we’ll pass the phone around and everybody adds a song. There always has to be some sort of connective theme and it’s always fun, and some weird shit will come up.

JW: It can be so enlightening. So many ideas and musical practices come from those moments. That moment of clarity is always nice. If I put on something, they’ll be able understand the drum tone I’ve been talking about. It’s a really lovely way of communicating.

_________________________________________________________

SAVING CAWTHRA

MW: The first set of songs on the EP that we recorded we did so quickly, and we wanted to almost force ourselves to take a long time — or at least what we thought was a long time! It was probably close to three months in total, but really spread out. We’d record a couple of songs, and then take two weeks off and think about it, and then go back in and write some more.

JW: It was all about the timing, giving ourselves and the songs time to breathe. We really value the live outlet of our band, and because of the inspiration from bands like Lightning Bolt, playing live is a big part of our sound. We treat it like practice. Going into it, we didn’t want to lose that, so we recorded things live-style and then went through the process of dialling stuff back or adding subtle things here and there.

MW: Oh boy, but did we struggle with the song “Cawthra”. We re-recorded half of it, more than once.

JW: There was a split in the band right away. Two of us really liked it, but for a while it was on the verge of not being considered for the album. [Producer] Dave Vettraino and I had a session where the rest of the band couldn’t come until later. It was the whole process of me trying to save the song with Dave! Saving “Cawthra”!

MW: We knew we had to step away from this song. But it’s like a painting that finished itself. The lyrics were maybe a little more fun than others on the album. The song is called “Cawthra” after a town outside of Toronto that we’ve passed through a couple times on tour, but it’s partly about writing really bad poems in high school. There’s a line like when someone attempts to write a sexy poem and says, “If you butter my bread, go to the edges.” That one really cracks me up.

_________________________________________________________

ON SWEATING AND FREEZING TOGETHER

MW: I was drawn to DIY because of the physical experience and the social environment. That’s been important to me since the beginning of my life, even with dancing. Being forced into physical situations that are strenuous has shaped us as a band, like basements that the rest of the band can’t stand in because they’re too tall, or sweating together, being frozen together. Also, the volume of our band is so loud that I have to scream, especially if the lyrics call for it anyway.

JW: I once read an interview with Chris Corsano, this crazy free jazz drummer who had toured with Björk. He said that music is all about feeling, about letting your entire being be wrapped up in the moment of making music. I think that’s always been important for us. It’s not just limited to noise rock or punk, that idea of feeling an emotion. At the end of the day, the best music is all about feeling.

MW: That makes me think a lot of Bart, too. Bart has weird theories on performance; when he plays, he definitely goes to a place. We joke around a lot because sometimes he’ll get a little snippy because he says you should play angry. [Laughs] Sometimes I don’t know where he goes. We’re all pretty high-strung people in our own way, and one time when we were playing a show that we were a little wound up about, we did this stupid improv warmup game … I can’t believe I’m telling you this. It was this hand game. And it was really dumb.

JW: That hand-slapping game.

MW: In a circle!

JW: It was like something you’d see a soccer team do before a game.

MW: I always prefer trying to get the group to go on a run together.

JW: If I’m playing a show and my shirt’s completely sweated out and my hands are really tired, I feel like I’ve put out the physical energy that translates into feeling like I put something out there that’s noticeable in a physical space. And the crowd is a huge part of the show. You have to feed off their energy. I’m really big on this drummer Milford Graves who talked a lot about how you can’t just be playing for yourself. That’s a very physical thing for me.

MW: The thread running through the whole album relates to our experiencing the terrain of the West Coast for the first time as a group and taking this alienated feeling and pairing it with the discovery of the terrain of the self. That physicality. It’s mashing person and place in one thing and talking about personality or identity as objects. I view “Middle Of” as fusing feminine insecurities and the terrain; it’s about giant holes in the earth and then also turning the van into a woman and talking about her physical limitations.

_________________________________________________________

THE SPACE IS THE PLACE

MW: The way we work the best is pulling things apart and putting them back together.

JW: Sometimes Miranda will send a voice memo of a riff or a song, and then I listen to it and it gets stuck in my head. And then when we come to practice, we’ll break it apart, inject our own feelings into it, and build it back up.

I record a lot in our practice space, even when we’re just jamming, just in case we want to keep those feelings and latch onto them. I like getting little riffs and little snippets of sounds and then just freestyling. In college, I played jazz band, and we’d perform every week for four hours, both standards and stuff that we would write and improvise on.

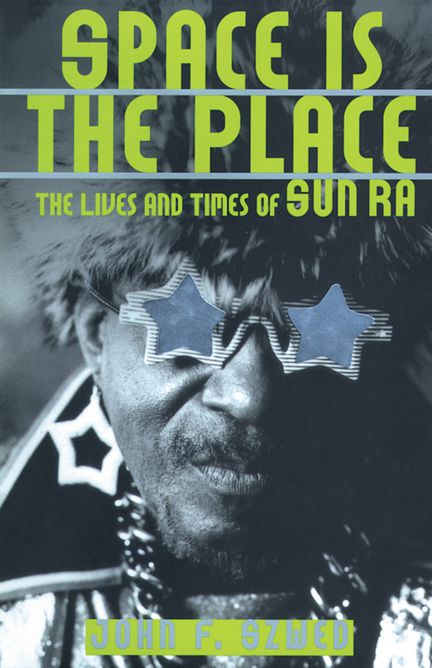

I’m just trying to feed off of the energy in the room. I’m a big big fan of Sun Ra. There’s a really great book written by John Szwed called Space Is the Place: The Lives and Times of Sun Ra, where Sun Ra talks about challenging the musicians in his band to put it all on the table, to improvise off the forms and the colors. That’s why I’m obsessed with recording stuff. If something does happen in a fleeting moment, I want to be able to capture that and turn it into something.

_________________________________________________________

Nothing Valley hits stores on October 13th via Wax Nine Records