File download is hosted on Megaupload

What’s weirder: Tori Amos singing happy birthday to you or Tori Amos singing happy birthday to you when it isn’t even your birthday?

In a New York City tower that overlooks Madison Square Garden – an arena that the singer-songwriter has been selling out for 20 years – Amos reflects on 10 meaningful moments of her decades-spanning career. As we chart her musical growth year by year through the early ’90s, she explains the uphill battle of releasing Boys for Pele, an album directly challenging her Christian upbringing, in 1996. I tell her this is my birth year – and that’s when one of the most established women in music sings happy birthday to a Taurus during Leo season.

This spontaneous celebration of birth isn’t too unexpected for Amos, who cultivates a palpable relationship with the natural world – her longtime friend and collaborator, the Sandman author Neil Gaiman, characterized Amos as a talking tree in his 1999 novel, Stardust. The North Carolina-born, UK resident has a spiritual connection with her surroundings that has yielded a prolific catalog ingrained in the exploration of ancient myth, human nature, and Earthly terrain.

Amos’ 15th album, Native Invader, marks a response to the nation’s changing political and geological landscape. In November, her intentions for the record changed when Donald Trump was elected president. The circumstance of sudden national unrest parallels the inspiration for Scarlet’s Walk (2002), a concept album sparked by the stories Amos heard on her post-9/11 US tour. Then, in January, Amos’ mother suffered a stroke, leaving her unable to communicate. Through months of grief comes Native Invader, featuring Amos’ music at its best: hypnotizing classical piano that confronts the political at its most personal.

_________________________________________________________

1974

At only 11 years old, how did you develop the self-awareness and confidence to understand what you wanted out of your musical training? How did dropping out of the Peabody conservatory shape your early years?

At only 11 years old, how did you develop the self-awareness and confidence to understand what you wanted out of your musical training? How did dropping out of the Peabody conservatory shape your early years?

Imagine when I’m in the ’60s, and [my brother] is 10 years older, practically, and those Beatles records are coming through the house, and The Doors … It wasn’t brought up to my father that The Doors were on that turntable before he walked in with his bible at six o’clock at night. Being exposed to all these different types of music, and going to the Peabody … Those are your building blocks. That was my first language. When I wanted to audition for the next stage [of the conservatory] with contemporary music, I was met with these strange looks, almost like I was doing whale sounds. And I think whale sounds are very beautiful. But I don’t think they would have liked those either. So, basically, I could see that they were shutting me down during the audition. And it was painful because I didn’t have another path carved out. Once you’re in the conservatory system, even though it’s preparatory, you are in a system. I just thought, “You are not my tribe anymore.”

_________________________________________________________

1990

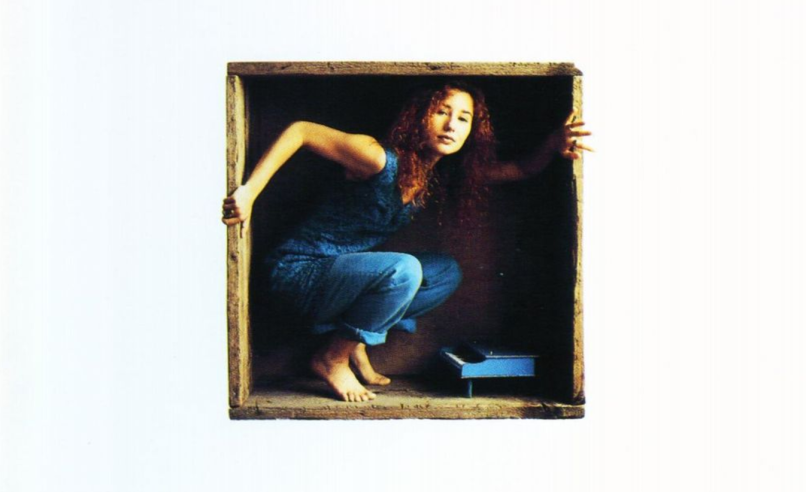

When you look back on the process of writing and recording Little Earthquakes (1992), your first album, what stands out to you from that period of your life? How did it feel to be caught in the middle of your first band (Y Kant Tori Read) folding and your solo career beginning?

There were a lot of rollercoasters during Little Earthquakes. When you face rejection, as I did with Y Kant Tori Read, I began to see that there were very few people in the music industry that were friends. That there are people that will be there for success, and may seem to be a supportive person in your life, but when you don’t achieve what everyone assumed was going to happen, and the play changes its story, not everybody wants to wait around. What usually happens is, not being invited anywhere anymore, and there is a sort of death that happens. It was a very face-on-the-floor time, lying on the floor, crawling to the piano … That was a moment of understanding, okay, I can create, and I don’t need all these people to create, and so I need to rely on myself here, and I need to develop some skills. And if I can’t do something, then I need to collaborate with someone who can.

Do you think that the music industry is still hostile now?

The industry really pit people against each other because there were only so many spots for women on alternative radio. If they were playing more than two on alternative radio, that was, for some people, two too many. But then you think, there are only two slots, and you’ve got, what, 20 records by women coming out that week? Well, think of what that environment … It’s built to not create a sisterhood of support. So I withdrew. The making of Little Earthquakes had become … This is not about radio anymore. I realized I have to wake up with my self-respect. I have to do this because I believe in it, and people will come. I’m not in my 20s anymore. I’m going to be 54 in a couple of weeks. And when you’re on your 15th album, you are in a different place than when you’re on your second, you know? You just are, because by then, if you’ve been around 25 years, then you’re making music and you’ve climbed many mountains. When the Boys for Pele reviews came out, Neil Gaiman said, “They’re wrong. It’s a blood-letting record by a woman confronting the Christian patriarchy. They’re not ready for it.” And he looked at me and said, “Some women are part of the patriarchy. Don’t get confused,” and I said, “I’m not confused. I know them well.”

_________________________________________________________

1992

What did it feel like to tour the world for the first time? How have your experiences while touring changed from then to now?

To feel the rush, my gosh! After the journey of getting Little Earthquakes through its different re-recordings — new songs coming in, new mixes — to when it was finally coming out and hearing that … Little did I know in 1974, I was going to turn pro when I was 13, but all that training and playing in piano bars, and doing that five nights a week at 15, six nights a week at 17, had prepared me for 1992. That tour, it went for … over a year. I had to learn. I got a crew in 1994 and buses. They knew what they were doing. I believe this: You’re only as good as your crew.

_________________________________________________________

1994

You helped found RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network) in 1994 and have been working with the organization for over 20 years now. What are you most proud of in your work with them?

The shocking realization in ‘94 was that you’re just trying to find a solution to something that needs a solution that you can’t do alone. And you realize the problem is bigger than you. And in that moment of helplessness, you pull your hair out and you just think okay, okay, so something has to get put in place. And that’s when people at the record label, particularly some of the women at Atlantic Records, joined forces. They were able to network with some of the people that are still at RAINN now and create a joined force.

What did you learn about balancing time between your music and RAINN?

There are so many heartbreaking stories, but then you realize – wait a minute – I need to hold space. And this took years to figure out. You hold a space, and you do your own work on yourself – the work you need to do – looking the person you’re talking to in the eye, and the look says it all: whatever they’re going through, they are capable. The last thing anyone wants is pity. But that took many meet-and-greets, many tears on both sides, people coming back to visit me over many months in their recovery. And when I say recovery, I mean in their continued recovery, because it’s a lifetime. And knowing some of these people now for 20 years, and then meeting people for the first time, even, you begin to know. It’s a lifetime. There are ups and downs. It’s been constantly learning since 1994.

_________________________________________________________

2001

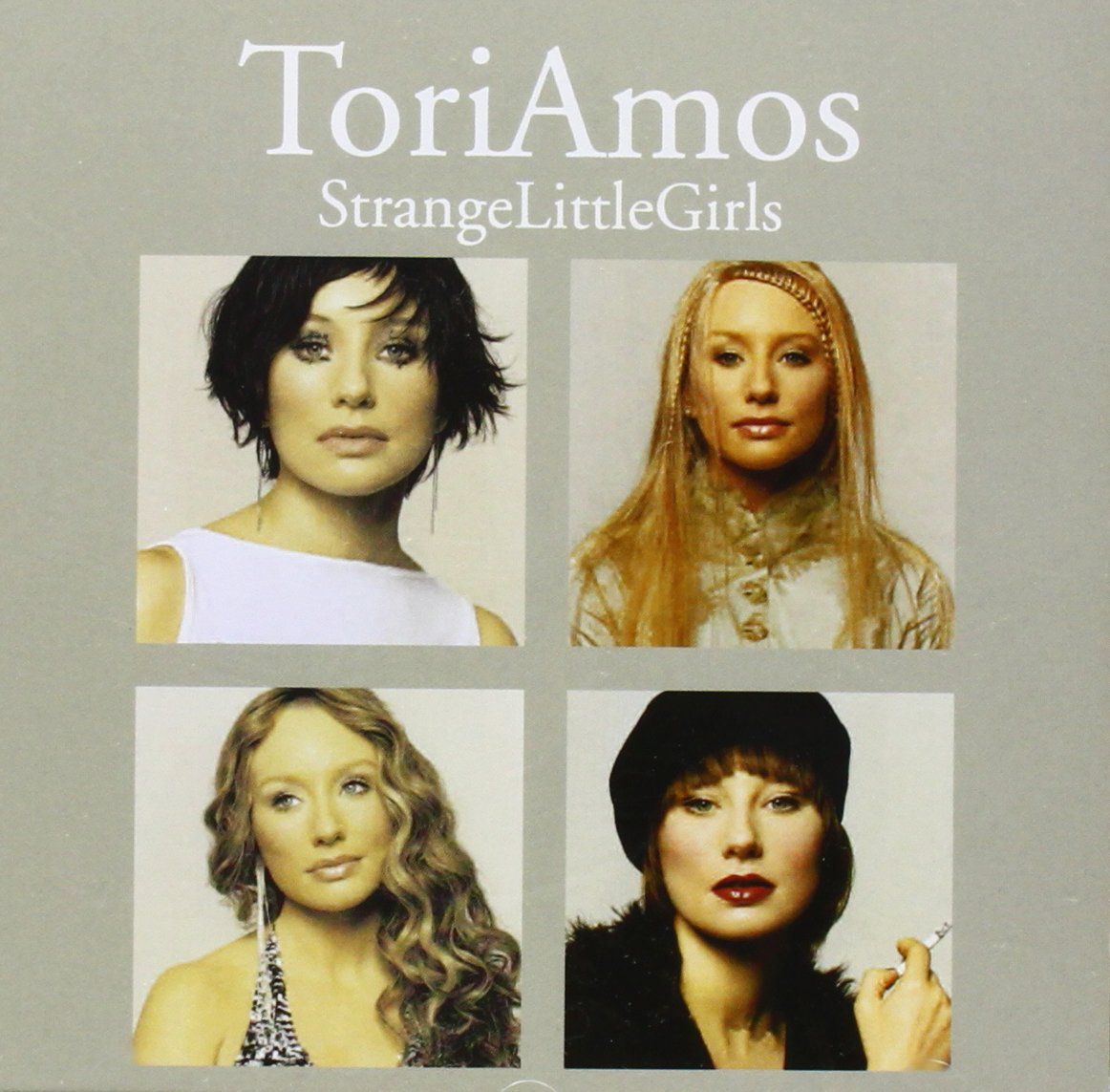

On Strange Little Girls, you rework popular songs by men about women – this record of inverted, gaze-shifting covers was your first release after giving birth to your daughter, Tash. Sometimes, motherhood is characterized as halting a mother’s career, but for you, it seems like having a child only added more depth to your work.

Hugely … We were down in a beach house in Florida. Tash had been born in Washington, DC, and we actually had a tour bus to take her down, because that’s just the choice we made. We went rock ‘n’ roll with Tash from Washington to Florida. Around Christmas time, Uncle Neil [Gaiman], one of Tash’s godfathers came down, and Mark [Hawely], Neil, and I were there, and I think she could’ve even been sleeping while we were just sitting in the living room talking about a place where the men are mothers, as creators, and the different songs of the time, and it was this collaborative conversation. In different mediums, [the album] came together. There were a lot of men involved, which I love that they wanted to be a part of something where the men are the mothers. And then, of course, the original songwriters, who were the birth mothers. I really enjoyed making that record, and I was in a bit of a spat with some of the powers that be at Atlantic at the time, so I just needed to be creative, and I do think that it was a way to try and find things in the music industry that I respected.

_________________________________________________________

2002

When you look back on Scarlet’s Walk now, in the Trump era, how has your perspective on American life and history changed? If this album was influenced by post-9/11 America, how has your perspective on 9/11 changed after so many years?

After 9/11, I had gone down to Florida to see Tash and make sure she was alright, and Mark was down there with her, but I waited a couple of days. I stayed [in New York], first, because I was going to be doing Letterman, and then he went dark. And then I went down there and got the call that he was going to have music … They wanted me to be the first music guest back. So, I jumped back on the bus after having been in Florida practically a few hours and turned around. And the key was that I was … we were travelling the country. Coming out of this hard-to-describe energy. And people were saying, “Don’t cancel the tour.” It seemed like people were saying, “We need a place to gather. We have to be able to gather.”

So Mark and I made the decision to take our year-and-three-month-old daughter on the road with us in this atmosphere, during that tour. People would come and visit me backstage and give information, thoughts – you need to write a record, it’s coming, you’ll pick up the seeds as you cross the whole country in this time after what’s happened, but you need to be open, because something else is happening. A reaction to what happened. It’s not just what happened; it’s the leaders that we have and their reaction. And that was a key kind of bit of advice for me to tonally get myself to a place where I could hear, then, the next person’s advice.

A Native American woman showed up at the show at the door in New Orleans. I have not seen her again, and she gave me a 35-, 40-minute monologue message about what that record needed to be, and I really took it as a prayer, as something I had to do. There are mirrors, clearly. When you see aggression, you recognize it when it happens again. And the thing, though, is that it can distract everybody from other things that are happening over here. This is happening, and then this is happening, and that is what Native Invader is really about – trying to listen to what the land is telling us, and ask myself, “Where are my intentions?” Because I have control of that.

_________________________________________________________

2007

On many of your records, like American Doll Posse, you relate something as ancient as Greek myth to contemporary life. How have your interests in mythology, religion, and history informed the way you write about your experiences?

The Robert Graves Greek Myths was by my side during the writing of Native Invader. “Wildwood” is very much the story of Persephone’s return after being in the underworld. Because I’m a minister’s daughter, maybe I ran to myth, just needing some kind of different perspective, and then I ran to the gnostic gospels and trying to get early Christianity before it became overtaken by a patriarchy. We’re seeing the word freedom being harnessed by American oligarchs, authoritarians, and women can be a part of that, but that has been really the force behind Native Invader – to reinvade these words, like “freedom.” Like “heritage.” We’re reclaiming these words, but for ourselves, as sovereign. Freedom is sovereignty. It doesn’t get to be owned by a party. It’s something that each of us has to reclaim for ourselves, and seeing these words getting twisted, like “liberty” … It’s been traumatizing.

_________________________________________________________

2013

For your 50th birthday performance, you donated proceeds to RAINN, which is a beautiful gesture about how the organization has stuck with you for decades. Did the 50 mark feel particularly momentous? What stands out to you about how you’ve grown as a person and musician over your career?

The thing is, sometimes, you can have these ups and downs. Menopause is a very tough teacher. I think writing Geraldines was to survive it and also realizing how culture sometimes makes it so that the elder women, now I know 50 isn’t elder, but I’m talking about culturally in the music business, 50 is elder. You look at how many male singer-songwriters, even if they’re encased in a band, have major record deals, versus female singer-songwriters over 50. That was staring at me like a loaded gun. So that made me question, why is it in our culture that it’s an aphrodisiac for men to age with a beard, and lines, and maybe a pot belly, and that’s still something we still want to hear? I love my sonic brothers. I respect them, but they have a very different route. And my brother-in-crime Neil Gaiman will tell you, it’s an absolutely different road. What is it in the culture that we don’t want to hear about our elders, our elder women, and their losses, and them moving into a different phase in their life? That really questioned me about where we put youth, because youth has amazing things, but it doesn’t have experience.

_________________________________________________________

2016

You wrote the song “Flicker” as the end credits for the Netflix documentary Audrie & Daisy. How do you navigate being an advocate against sexual violence for so many years when that work can often be so emotionally taxing? What have you learned along the way about how to balance your activism and your music, which can also be an emotionally fraught space?

This is what I learned through Bonni (Cohen) and John (Shenk), the directors – this is not just about Stanford, or Daisy’s case that went viral, and Audrie, her case … this is pervasive. Sexual violence is not going away. It’s almost as if society is becoming numb to it … they seem fatigued by the issue. That’s why “Flicker” needed to be something that … I was travelling the states in the fall talking about this issue, and I felt it was important, having met Daisy, then having met Audrie’s mother. I heard from them about the journey that they had been on, and then of course, realizing that this is in our schools. This is not something that happens once in a while. But it seems to be the rule more than it is the exception. And that was terrifying if you’re a youth today. But then there’s healing. And there’s the work. In Ireland, when someone dies, there’s the keening and the women will come, and they’ll sing in your ear so that you can begin to release all that you’ve been holding on to that’s paining you. And I think that’s the idea of listening to the stories, playing music, finding ways to help people in their next step.

_________________________________________________________

2017

You’ve said that Native Invader is taking a more political turn due to recent events in the world and in your life. What is a key message you hope to convey through this album? Do you think that living and recording in the UK has changed the way you think of American culture?

The UK, we record there, but I don’t write in the UK. I take pilgrimages to places to activate … to find the muses. Last year, we went to the Smokey Mountains, and the Carolinas, and on the Tennessee border, where my mom was from. I sat by the rocks and sat with the waterfalls and sat with the mountains and went to the old mounds and said, “Any song lines that want to come, show me the way.” Already, the debates were going with the energies out there – there were conflicts, how people were talking to each other wasn’t a respectful, “Listen, people may disagree, but this is how we behave towards each other…” No. That was already out the window.

I spent a lot of time through January in the states, because my mother was ill. She hadn’t had her stroke yet, and I was talking with her about the ancestors in the mountains and the stories she remembers. When I say the mountains, when I was in the mountains last June. Little did I know that would be the last time that she was ever able to … express a thought that isn’t trying to sing a hymn with you. But it’s a severe stroke. But she’s there – she’s trapped. She can’t write – she’s paralyzed.

So, it’s frustrating for her, and almost to see her captive, and to see America captive as Earth mother. Mary being captive, and then the idea of Lady Liberty being captive, because freedom is a fascinating word that’s getting used a lot right now, but we have to invade it, because it’s being twisted into something that’s for a few people, and then everybody else is subjugated, and some of us don’t even know we’re being groomed. As they say, not everybody knows they’re working for the Russians when they’re working for the Russians, hence the song “Russia,” on the record.